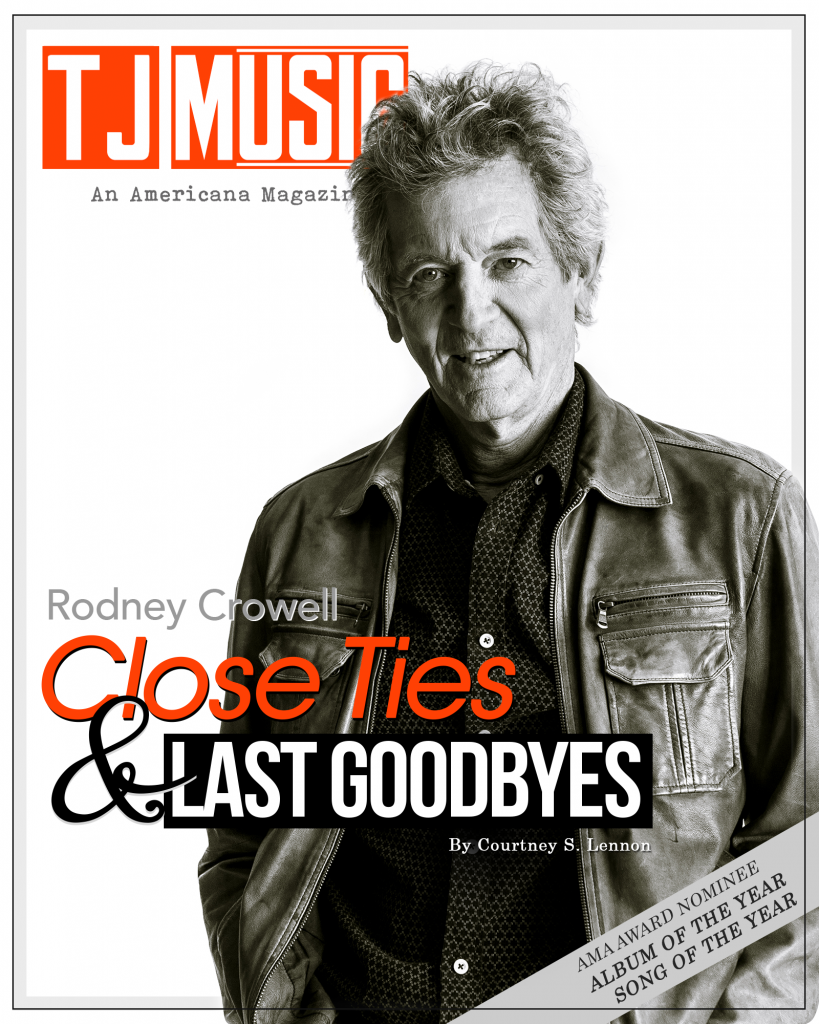

Rodney Crowell is at home in Franklin, Tenn., about 30 miles south of Nashville. The East Houston native, speaks with a polite southern drawl, sounding like a Texas gentleman. At the age of 67, there is wisdom in his voice that carries a cool calmness, complimented by his sharp wit. Crowell, whose 1988 release, Diamonds & Dirt, produced five no. 1 hits, is at his desk, the place where he does what he calls, “the work.” Sitting up on the mantel, are two Grammy Awards. In 2014, Old Yellow Moon, a project he collaborated on with longtime friend, Emmylou Harris, won Best Americana Album. In 1990, he won Best Country Song, for “After All This Time,” a symbol of his mainstream success.

“I had 15 minutes of it. I had my 15 minutes,” he says.

It isn’t the accolades that are gratification for his career as a singer-songwriter. Rather, it’s writing and looking at the big crop of trees that are out in his yard. “If I’m home and it’s the morning and something isn’t trying to steal my time, I’ll be right here writing. It’s the work. Doing the work. That’s more important to me than anything. Everything else is just a byproduct. I’m grateful that I’ve managed to raise a family and keep a roof over our heads, being an artist. That’s success to me, that’s all that I ever wanted.”

East Houston Blues

East Houston blues, scale of one to ten

Bout a nine and a half is where it’s always been

It’s in the drinking water and in the bar ditch mud

East Houston blues, gets in a poor boy’s blood

-Rodney Crowell, “East Houston Blues”

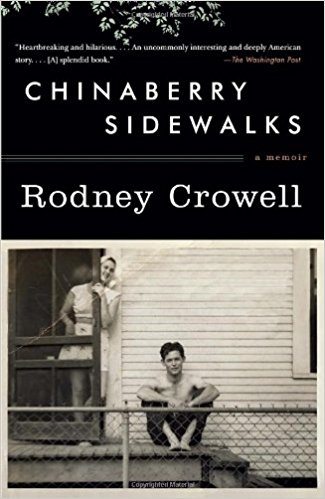

Crowell has already penned his own life story. His latest release, Close Ties, is a continuation of his 2011 memoir, Chinaberry Sidewalks, which chronicles his childhood, growing up in East Houston. In the beginning of the book, he recalls the events of New Year’s Eve, 1955, when he was just 5-years-old.

Crowell has already penned his own life story. His latest release, Close Ties, is a continuation of his 2011 memoir, Chinaberry Sidewalks, which chronicles his childhood, growing up in East Houston. In the beginning of the book, he recalls the events of New Year’s Eve, 1955, when he was just 5-years-old.

He writes, “I’d been privy to the shadowy undercurrents detailed in my mother and father’s all-night shouting matches, long enough to know that drunk husbands and wives swapping two-steps with other drunk wives and husbands, though a time-honored Texas tradition, was anything but harmless fun. I could never grasp what she accused him of doing with Lisa May Strickland or Pauline Odell, but I knew by her disdain for the word ‘screwing,’ that nothing good ever came of the deed. And it got more complicated when she started screaming about how he’d even screw a light socket if one could spread its legs for him. Grown-ups are weird.”

From there, he touches on a story he heard growing up. When his mother was eight months pregnant with him, his father whipped her on the stomach with a belt while she was standing naked in the bathtub. Though he wasn’t yet born, the scene was ingrained in his mind. While the book details the sometimes-tumultuous relationship his parents had, his view of his father, far different from what one would expect from reading most of Chinaberry Sidewalks. His perspective, at the other side of childhood, shows his maturity. He writes and speaks about his father, with empathy and admiration.

“He was an enigma,” Crowell says. “He was a better singer than me. But he only had a seventh-grade education. He grew up on a sharecrop farm in Kentucky. I wrote about them living in a sheep shed. They did. For whatever reason, he was unable to visualize the possibility of taking his gift and really turning it into what he wanted it to be. So, he got stuck with a big dose of egomania that had no place to go. He was a frustrated artist. I think, had he found his way to getting backing and recording and gotten some songs, he probably would have been a big star. He was handsome. But it wasn’t his destiny the way it was mine. He wasn’t ever going to write like I do. I got that from my mother. My mother was a storyteller.”

Though prior to the release of Chinaberry Sidewalks, Crowell had recorded 13 albums, becoming an author influenced his approach to songwriting. During the process, he went back and edited the book, to the point where he couldn’t guess how many times he went through it.

“I discovered the productive aspect of revision,” he says. “Up until the late ‘90s, I always relied on my swagger and inspiration. I’m a natural born songwriter, so it would come to me and I’d write songs. I’d write two-thirds of a really good song that becomes a hit and I think, ‘God why didn’t I do a better job on that last verse?’ With those kinds of experiences, eventually, I became far more conscious, that I’m not letting anything go until I’m sure that’s the best I can get it.”

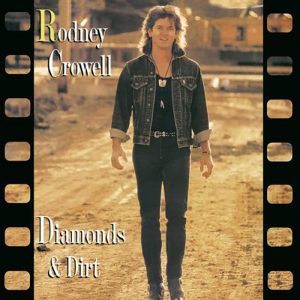

Crowell is still proud of his most successful album, Diamonds & Dirt, which is filled with solid, catchy country songs. But today, he believes that his 2001 release, The Houston Kid, and everything thereafter, is work he can really stand behind. It doesn’t make him “cringe.” In the song “I Don’t Care Anymore,” from Close Ties, he pokes fun at his getup on the cover of Diamonds & Dirt. He sings, “A real friend tried to tell me man, with all respect it’s true / The time to put away these things is long since overdue.”

Crowell is still proud of his most successful album, Diamonds & Dirt, which is filled with solid, catchy country songs. But today, he believes that his 2001 release, The Houston Kid, and everything thereafter, is work he can really stand behind. It doesn’t make him “cringe.” In the song “I Don’t Care Anymore,” from Close Ties, he pokes fun at his getup on the cover of Diamonds & Dirt. He sings, “A real friend tried to tell me man, with all respect it’s true / The time to put away these things is long since overdue.”

“I just think it’s silly,” he says. “What am I, 25 years older now? I look at that guy and I go ‘Hey dude, you know Dwight Yoakam owned that shit at that time. He had his hat over his eyes, got into those skinny leather britches, had his collar turned up and I mean, he owned it.’ Then, there I am, walking down the road. I mean, who dresses up like that with silver tipped boots to walk down a dirt road? It’s fake. I think, ‘Jesus Christ man, you thought you were a real, true artist at the time. But, you were posing.’ I think it’s funny.”

Today, Crowell looks every bit like the Texas statesman he is. His attire, typically a fedora, button up shirt, jeans, a blazer and sometimes, a pair of black shades. His affection for country blues that has developed over the years, telling as to how he views maturity as an artist. The opening track on Close Ties, “East Houston Blues,” chronicles his early life. The song, with its raw sound, conjures up a 1930s vibe, containing slide guitar, a steady beat and upright bass.

“There’s something about it that moved me to take into consideration that it’s really grown man stuff. Lightin’ Hopkins is a dose of grown man. I said ‘I want to create more from that place, I want to grab it by the ears a little more.’ It was a very subtle thing. As a kid growing up my reference for blues was Hank Williams.”

Nashville 1972

I had a dog named Banjo and a girl named Muffin

I’d just blew in from Texas and I didn’t know nothing

I found my way around this town with a friend I made named Guy

Who loved Susanna and so did I

–Rodney Crowell, “Nashville 1972”

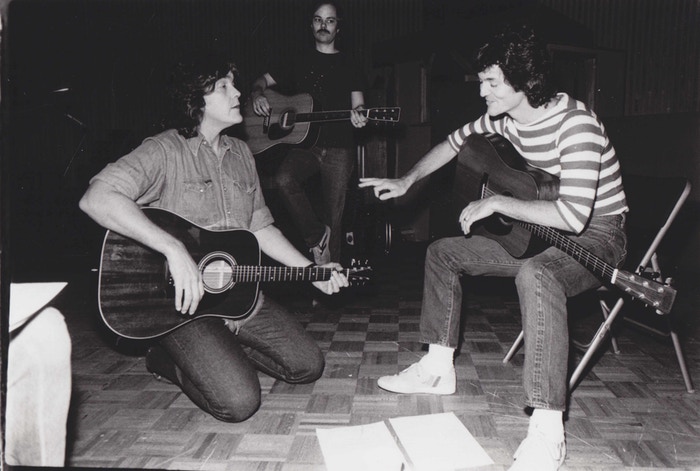

Back in 1972, when he moved to Nashville, Crowell was not the adept craftsman he is today. That wasn’t his role at the time. He was just a kid from Houston, who would unknowingly walk into a den of songwriting mastery, where he was educated on the dynamics of the art.

“What drew me to Nashville? The pied piper,” he jokes. “I was supposed to go have this career in music and I had no game plan. I knew that in Nashville, they had recording studios and people who make records. From where I was in Texas, it was the closest place. So, that’s where I’m going.”

When he first got to Nashville, he was a fresh-faced 22-year-old with a head of moppy black hair, who, in his paisley shirts and jeans, looked like a 1960s folk singer. Upon his arrival, he didn’t have a place to say. So, he lived out of his car from August until Christmas time. “It was great,” he says.

While he was hanging around Centennial Park, located two miles east of downtown, he met a gypsy and a tight-rope walker from Upstate, N.Y. They told him that he should talk to songwriter, Guy Clark, but he didn’t wind up going to see him. After Crowell got a job bussing tables, he moved into a “run down shack on Acklen Avenue,” with bass player, Skinny Dennis Sanchez and poet, Richard Dobson. It was there, that he met Clark.

“He was passed out, face down on my little bed,” Crowell says. “I was gone. It was in the middle of the day. He was crashed out. His boots were hanging off the bed. His wife Susanna said, ‘We heard you were in town and we came around to see who you are.’”

Crowell’s friendship with Guy and Susanna Clark, developed fast. It was his relationship with Susanna, that would eventually lead him to have deep friendships with Emmylou Harris and author, Mary Karr. He learned that he could be close with women and collaborate with them, without there being a romantic relationship.

“Susanna was 11-years-older than me and I wanted to have a conquest with an older woman,” he says. “And she just said ‘Hey, why don’t you learn how to be somebody’s friend or something first.’ It caught my attention I thought ‘Oh really?’ I was 22-years-old, so I wanted to get in her pants. She was the first woman who turned me around, where I could say ‘Oh, I can be your friend.’ And I became her close friend.”

The apartment on Acklen Ave., became the hangout spot for late night songwriting. Crowell, Sanchez, Guy and Susanna Clark, were among those who participated. They would stay up all night, talking, singing and playing guitar. Then, eventually, the right moment would “trip” at 4 a.m.

“We’d say ‘Okay, that’s a song.’ And we’d started messing with it. It could happen anytime. It could have happened at noon. It was 24 hours a day. Get your receptors out there and your antennas to pick up this stuff, your awareness of the art and be ready. Now, whenever inspiration hits me, I move everything out of the way and do it. I write in the morning, night and middle of the day. It’s all the same.”

Crowell, along with Steve Earle and the rest of the young songwriters, had to develop. Even if it wasn’t said, they wanted to out write each other. It was Susanna, who kept the group grounded.

“She just wasn’t impressed by our macho competitiveness. ‘I’m going to write a better song than you. I’m gonna get Susanna’s attention or Guy’s attention.’ Townes Van Zandt had everybody’s attention, because he wrote such great songs. There was enough competition around to make it really healthy. But Susanna would just look at us and say, ‘You guys are so silly. You think art is about proving something.’ ‘What is it?’ I’d ask. And she’d say, ‘If you don’t know, I’m not gonna tell ya.’”

In 1973, Crowell had a casual conversation with Guy Clark, who said, “Hey man, you’re talented. You can be a star if you want to. There’s no harm in that. Or, you can be an artist.” Crowell responded, “I wanna be an artist. That’s what you are. I want to be one of those.'”

In 1973, Crowell had a casual conversation with Guy Clark, who said, “Hey man, you’re talented. You can be a star if you want to. There’s no harm in that. Or, you can be an artist.” Crowell responded, “I wanna be an artist. That’s what you are. I want to be one of those.'”

“And it was just a moment. It meant a lot to me and it was actually conscious shifting. But it wasn’t a big deal pronouncement. It got me thinking ‘You know, I really do want to be an artist. So, it’s my job to figure out how that happens.’ Now, 44 years later, I’m still working on that small moment. ‘Yeah, I’m an artist, I’m going to do this. How do I do this?’ It’s the reason I get up in the morning.”

For Clark, despite the difference in experience, he didn’t act like he was any different than the less established songwriters who were still learning the art. That wasn’t his personality. He was a teacher to Crowell, but didn’t see himself as one.

“I would call him a mentor,’ but if I ever mentioned it to him, he would say ‘Bullshit.’ Guy didn’t go for that kind of thing. ‘I’m not watching you while you try to ride a bicycle without training wheels. It’s a level playing field for everybody. You gonna write a song or not?’ he’d say. And I’d say ‘Man you were are an influence on me.’ He’d say ‘Bullshit.’ But underneath that gruff attitude he was very generous and knew exactly what he was doing.”

In a 2012 interview with TJ, Clark called Crowell his “cheerleader.” Crowell was there, encouraging him to write songs when his health was failing. Crowell would say, “Come on man, let’s write something.” But on May 17, 2016, after a lengthy battle with cancer, Clark passed away.

“Now wherever he is,” Crowell says, “he’s probably somewhere being an artist, saying ‘Yeah I wasn’t a mentor to that guy.’”

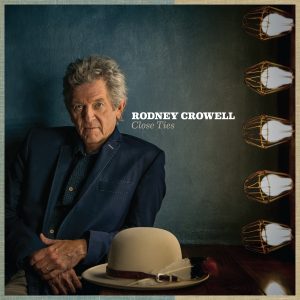

Close Ties

In just about a week, Crowell will be in Nashville for the Americana Music Association Honors & Awards, which will be held at the Ryman Auditorium on Sept. 13. He has won five Americana Music Awards, including one for Lifetime Achievement in Songwriting.

In just about a week, Crowell will be in Nashville for the Americana Music Association Honors & Awards, which will be held at the Ryman Auditorium on Sept. 13. He has won five Americana Music Awards, including one for Lifetime Achievement in Songwriting.

“There’s no doubt that the genre’s been really nice to me,” he says. “I’ve been on the board of directors for years. I don’t know how many. But, they’ve awarded me and I have to be grateful for them, because right around the time I made The Houston Kid, was when they came into focus. So, they’ve steadily defined a genre that I have worked my way into, naturally.

It put a frame around what I was doing. Emmylou and I worked together and she said, ‘Americana music, they finally gave a name to what we were doing in the ‘70s.’”

Crowell and Harris have won three Americana Music Association Awards together. After leaving Nashville, in the mid ‘70s, he went to Los Angeles to play with Harris in her Hot Band, which included Glen Hardin, James Burton and Emory Gordy, who were also playing with Elvis at the time.

“I love, L.A.,” he sings the Randy Newman line and laughs. “Or, I did. In the ‘70s, L.A. was happening. For me it was. I became a good songwriter while I was in Nashville and that’s what got me to L.A. with Emmy. But in L.A., as a songwriter, I got into the musician scene there. I started hanging out with musicians, recording and learning arrangements. I became a producer. If I hadn’t gone to Los Angeles, I’m not sure I would have ever been a producer. Hanging out with those musicians, I learned to speak the language of arranging, which gave me a platform to record and make records. I produced too many of my own records,” he laughs. “I don’t like to do it so much anymore.”

Among the albums Crowell has produced for other artists, are Rosanne Cash’s 1986 release, Rhythm & Romance, which landed him a deal with Columbia Records. He also produced Guy Clark’s 1983, album, Better Days. For Close Ties, he opted for Kim Bruie, head of A&R for New West Records, his current label, to produce the album. Four-time Grammy Award winning artist, John Paul White (the Civil Wars), who appears on the album, talks about Crowell’s approach to letting another producer take the reins.

“He was very hands off. I don’t know if that’s normal routine or if he’s a micro-manager, but I just know in my situation, he let me do what I do and didn’t really hold my hand. I tend to flourish more in those situations. He definitely was at the console, talking to me, talking me through it. But more or less, he just gave me free reign to do whatever I wanted to do.”

It Ain’t Over Yet

This year, at the Americana Music Honors & Awards, Crowell is up for Album of The Year for Close Ties, as well as Song of the Year for “It Ain’t Over Yet,” which was recorded with his ex-wife, Rosanne Cash and John Paul White.

This year, at the Americana Music Honors & Awards, Crowell is up for Album of The Year for Close Ties, as well as Song of the Year for “It Ain’t Over Yet,” which was recorded with his ex-wife, Rosanne Cash and John Paul White.

“Over a period of a couple years, I was writing songs for Close Ties,” Crowell says, “and just a rash of people left the planet.”

The track before “It Ain’t Over Yet,” which Crowell admits is in apt succession, is “Life Without Susanna.” The lyrics chronicle his relationship with Susanna Clark. After Townes Van Zandt died on New Year’s Day, 1997, Clark became a recluse. She developed a back ache and went to bed for the rest of her life. A woman who Crowell once had a vibrant relationship with, was far different from the person he once knew.

“I tried everything. Tough love. She’d be lying in bed, stoned on pain pills, smoking cigarettes and say, ‘Come here and talk to me.’ And I’d pull a chair up in the hallway just about 30 feet away and I’d say, ‘I’m going to talk to you from here, I’m not coming in there.’ And she’d wait me out. She was more stubborn and stronger than me. ‘Susanna why don’t’ you get up out of this bed?’ She’d just give me that look and say, ‘You know, I love you but you’ve never been able to get me to do exactly what you want me to do.’ It’s probably one of the most honest songs I’ve written. That was 40 years of love.”

Susanna Clark passed away on June 27, 2012. After her death, he tried to write “It Ain’t Over Yet” with Guy Clark, but Clark’s health didn’t permit it. So, Crowell wrote the song for him. He framed it as a narrative, a three-way conversation between himself, Susanna and Guy.

On the bridge, Rosanne Cash sings Susanna’s part, “Silly boys blind to get there first / Think of second chances as some kind of curse / I’ve known you forever and ever it’s true / If you came by it easy, you wouldn’t be you.”

“Boys, we’re always trying to pull out our sword and prove that we can slay the dragon,” Crowell says.

Singing the chorus on the song, is John Paul White. The Alabama native, was asked to be on the record, by producer Kim Bruie. Prior to recording together, Crowell and White first met at the Grammys in 2012.

“I didn’t remember [meeting at the Grammys],” White says. “I was with the Civil Wars. We were getting ready to get on stage and he was standing right there. I guess he could sense I was tense. He said, ‘Let me take your guitar for you.’ I looked at him and smiled. But I don’t remember that at all. It was like selective amnesia, because I would have freaked out if I’d realized it was him.”

Crowell and White consider the recording session for “It Ain’t Over Yet,” their first real introduction. “That was kind of a love at first sight thing,” Crowell says.

“I would say the same thing,” White says of Crowell. “I feel like when I met him, as he said, it was instant. Like we had known each other for a long time. I feel like, maybe this is presumptuous on my part, but we’re a lot alike. We grew up with the same values and he has a lot of the same wants and needs from his music and from others. I really sat on that and just felt like it was a kindred spirit kind of thing.”

“When I was asked to sing on his record,” he continues, “I was terrified, but of course I said ‘Yes.’ When I got there, I didn’t realize that I was going to be singing the choruses by myself. I thought they were going to have me sing harmony on something. They played me the track and when it got to the chorus, it was nothing. I told him ‘It’s gonna be hard to sing harmonies without your vocals.’ And he said, ‘Oh no, Hoss, you’re going to be singing that chorus.’ So, I didn’t have time to get really violently ill before I did it.”

When White went into the recording studio, he also had no idea what the song was about. He wasn’t told that the chorus he was singing, is Crowell speaking to Guy Clark. White’s interpretation, was exactly what Crowell wanted. On the chorus, White sings:

“It ain’t over yet, I’ll say this about that

You can get up off the mat or you can lay there till you die

It ain’t over yet, here’s the truth my friend

You can’t pack it in and we both know why

It ain’t over yet.”

Those lines are every bit the representation of Crowell’s role as Clark’s cheerleader in the years before he passed. The last song Clark wrote, was with Crowell. Clark, had an idea for something and showed it to him. He knew Crowell was interested in country blues at the time and asked, “You think we can make this something like that?” Crowell replied, “Yeah, we can do it.”

“He didn’t have much energy left,” Crowell says. “But I’d say ‘I got this,’ and he’d say ‘I got this far’ and I’d say, ‘What do you think of this verse?’ Eventually we knocked out the song. I think it was the last one. But if I know Guy, there was probably someone else trying to get him to the finish line. But it’s a good song. It’s something I’ll record.”

Most recently, Crowell collaborated with White. Their first co-write together, “Don’t Think That I Can’t Feel You When You’re Gone,” a gentle, sparse acoustic track, recorded for the Luck Mansion Sessions, which was released at the end of August. Their relationship, one that has developed fast. When they first walked in to co-write together, they had the exact same guitars, which was strange. They were tiny black Gibson parlor guitars from the 1930s. The odds of them both having those same guitars, was very unlikely.

“We got a laugh out of that,” says White. “We just started playing and I started singing and things just started falling out. That’s how I typically write. I wrote for the Nashville industry for quite a while and it was all based on ideas and themes and clever word play. I’d usually go in and write, ‘I’ve got this theme, or this chorus or this hook.’ And it wasn’t like that at all with him. We walked in and really, just made small talk for no time and bam, we were in it. An hour and a half later, and we were done. That doesn’t normally happen on a first co-write and especially with someone whose been your hero most of your creative life. So, it was a really great day.”

“He’s a gentleman through and through,” Crowell says of White. “And I like gentlemen, I like to be around them.”

“I’m glad to hear he said that,” White says. “I kid him that he’s just riding my coattails to make money, that I’m really the talented famous one of the two of us. And he lets me believe that, so it’s a good relationship.”

Whereas Crowell started out as a young songwriter, falling into the lap of Guy Clark, today, he has become the artist he set out to be at the start, whether he believes it or not. With a career that spans 44-years, he still continues to grow. He possesses the same intuition that he admired in other songwriters, feeding off the people he works with and vice-a-versa. He was once learning how to write with other artists, but today, he is a shining example and master of it. After working with Crowell, White is in a different mode on how he wants to approach songwriting. He has a collaborative spirit, a fire that was lit working with Crowell.

“I want to aspire to have the career path he’s had. That’s a perfect road map for me, in my opinion,” White says. “He might not like it, but for me he’s just a shining example of the kind of artist I’d like to become.”

On Sept. 13, at the Ryman, Crowell, Cash and White will perform “It Ain’t Over Yet” together. The song, one that is hard to listen to without feeling the deep emotion that Crowell so honestly penned. It is a moving goodbye, to two of his closest friends, who were there with him as he set out on the path to become the master he is today.

“I’ll be the terrified dude at the side of the stage,” says White. “Because I know how much that song means to everybody involved and I don’t want to drop the ball.”

AmericanaFEST Schedule

Americana Music Association Honors & Awards – Wednesday, September 13th at 6p – Ryman, Nashville

Rodney Crowell – Thursday, September 14th at 6p – Downtown Presbyterian Church, Nashville

rodneycrowell.com | fb | buy

Courtney S. Lennon

Latest posts by Courtney S. Lennon (see all)

- Billy Joe Shaver: August 16,1939 – October 28, 2020 - November 2, 2020

- You Are About To Become Involved With Van Dyke Parks! - July 13, 2020

- The Hero of Texas Music History - July 23, 2019