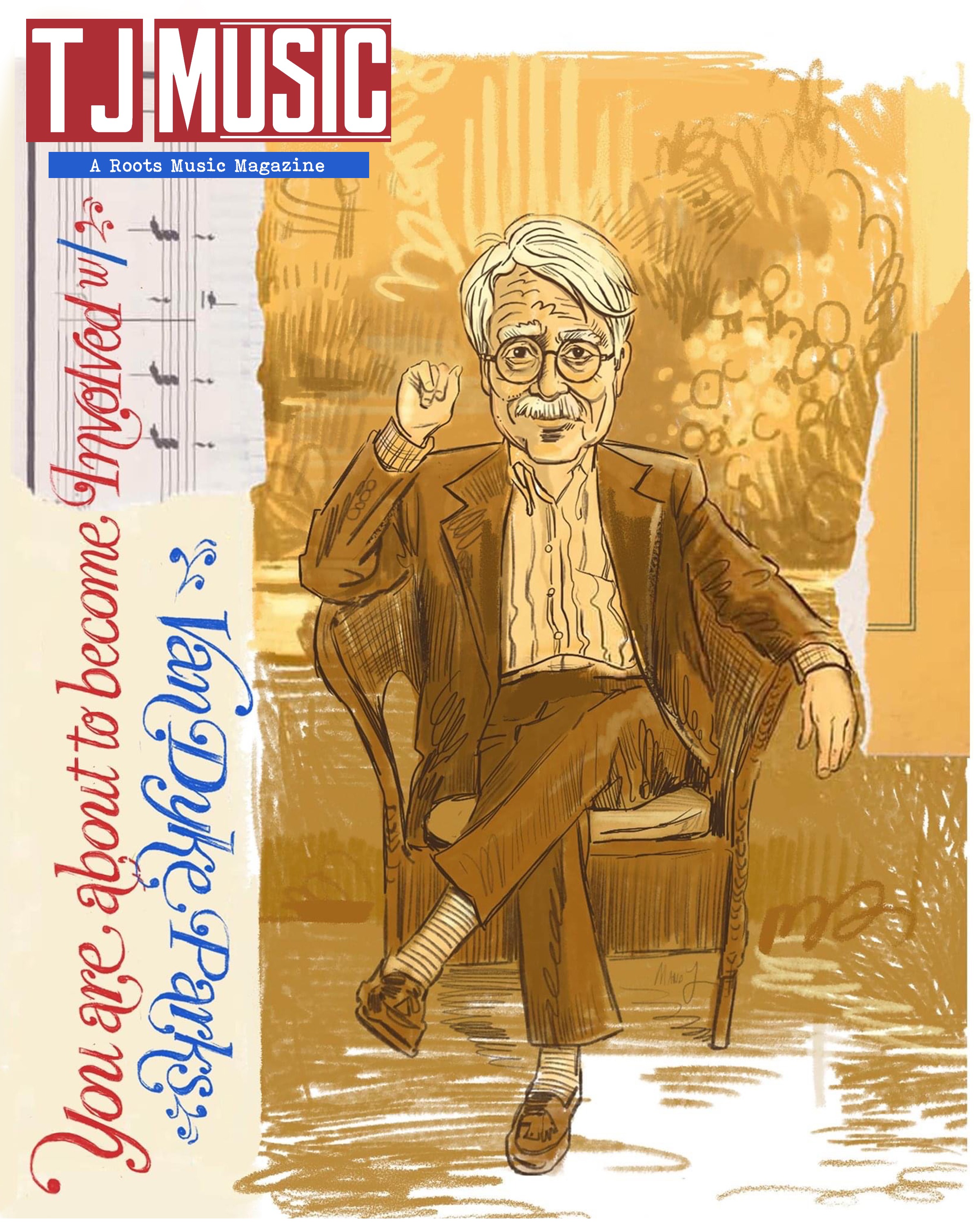

You Are About To Become Involved With Van Dyke Parks!

Words, Courtney S. Lennon

Illustrations, Mandy Newham-Cobb

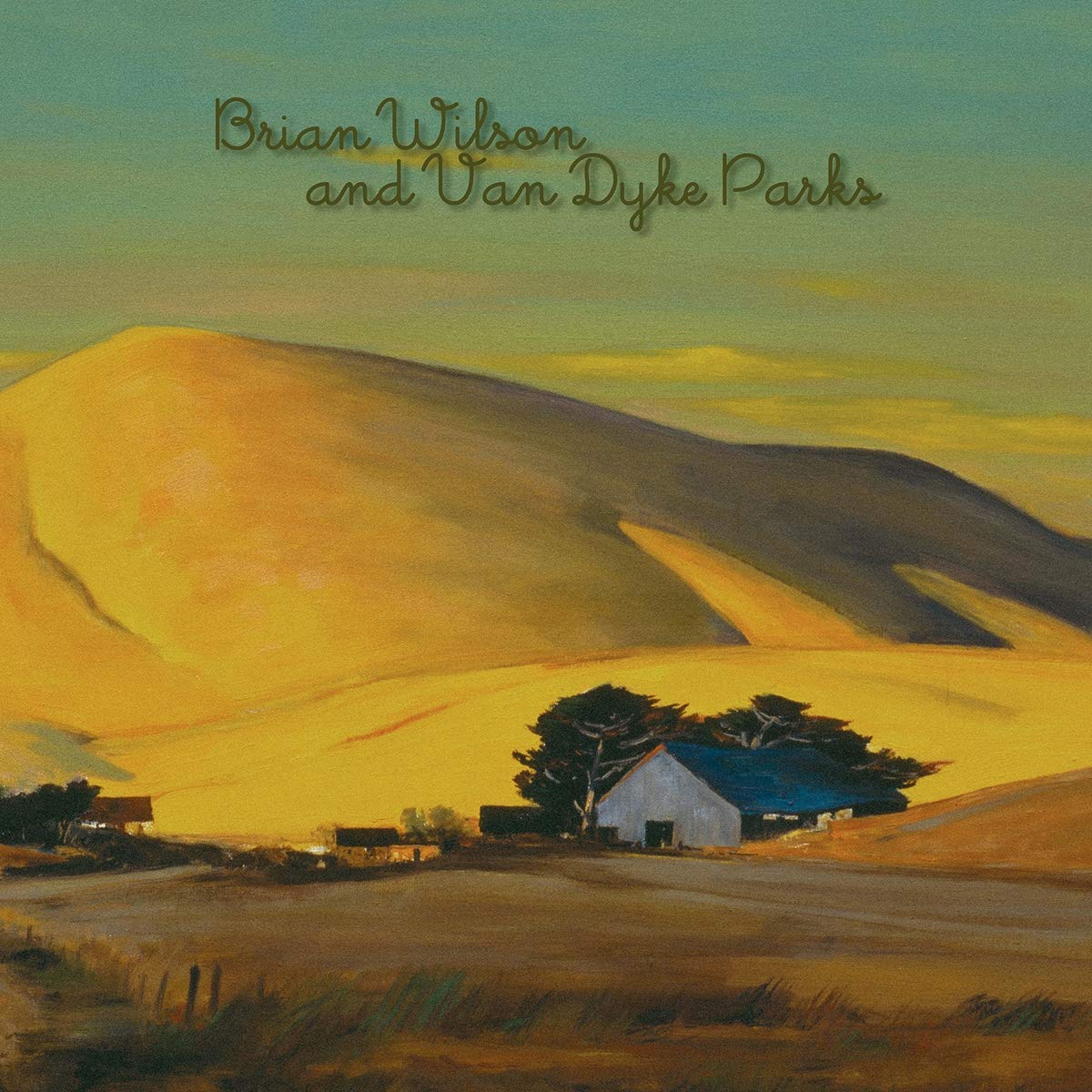

It’s eleven in the morning on a mid-June day and Van Dyke Parks is at home in Los Angeles. He’s doing press for the recent Omnivore Records re-issue of his 1995 ode to the Golden State, Orange Crate Art, a Brian Wilson co-bill which aptly features the Beach Boys legend on vocals. Mid-pandemic, Parks has requested we conduct our interview over FaceTime.

“Hello Mr. Parks!” I say with enthusiasm as he appears on video.

“Hello,” he says with a smile.

“I’m Courtney. How are you?”

“Courtney. Fantastic. Life is a snap. Where are you?”

“I’m in Buffalo.”

“I love that area,” Parks says. “Living in California, I miss forsythia, the first crocus, the first robin…skies with cumulus clouds. Real clouds.”

“I used to live in L.A. You do miss the seasons change.”

“How can I possibly trash your career?” he kids.

“I’m just doing a feature on you,” I laugh. Right away, I’m comfortable talking to him. Parks is more than forty years my senior, and not trying to intimidate me. He’s friendly. I thought he would be. This wasn’t our first correspondence.

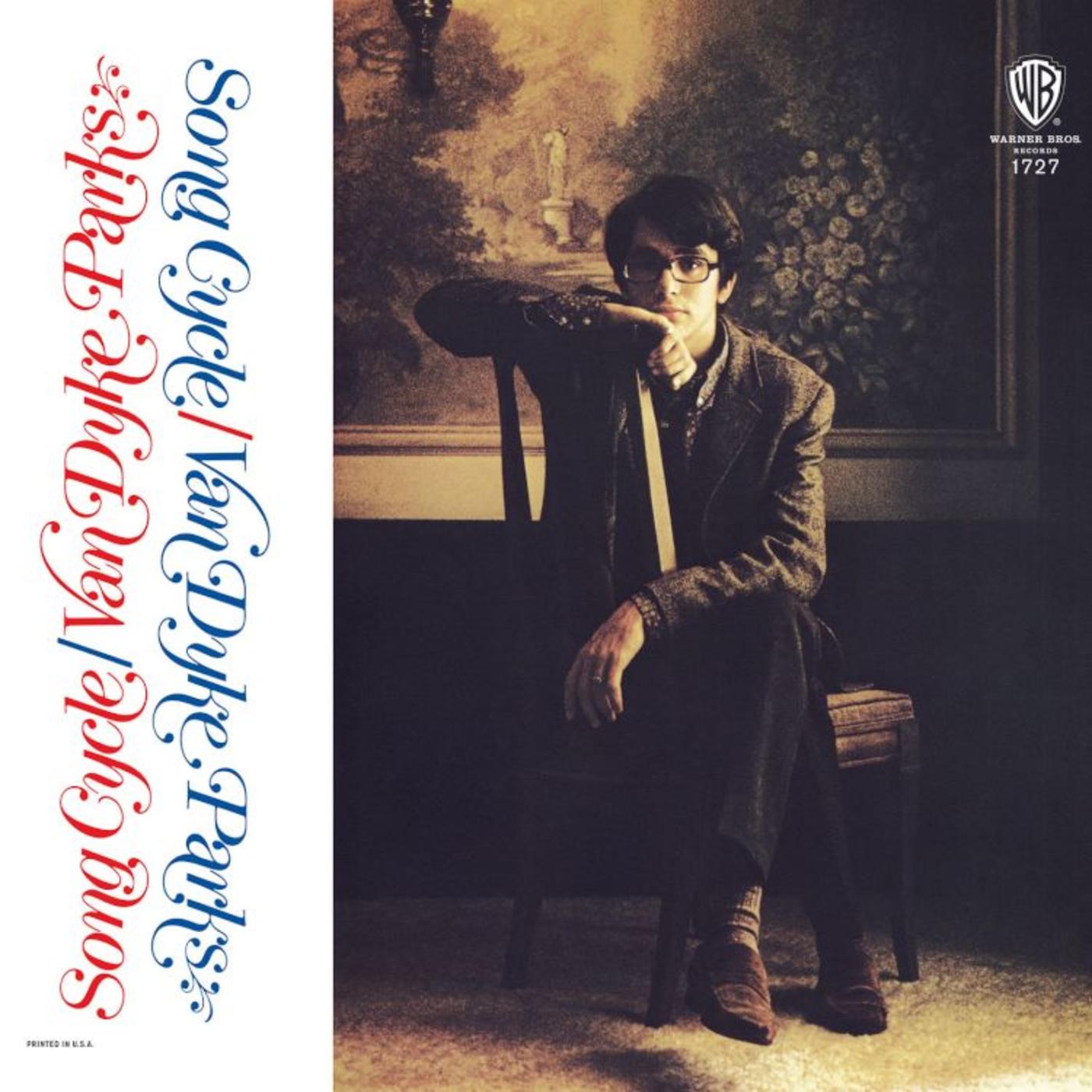

“I wanted to say something to you,” I start. “You won’t remember this, and you shouldn’t have to. But when I was nineteen years old, about sixteen years ago, I sent you the only fan letter I ever sent anyone in my life. The whole thing was about how much I loved Song Cycle. How much it meant to me. You responded. I thought it was just so kind. I was so impressed. It meant a lot to me.”

“Well that’s very nice of you,” he says sincerely. “It was a feeble attempt to direct my life at empowering others around me. That’s what it’s all about.”

It’s true. What a cool thing as a teenager for your hero to respond. It was a great lesson in humility. Of course, Parks has made a habit of empowering others through his career, working alongside peers like Brian Wilson, Lowell George, Randy Newman, Harry Nilsson, Three Dog Night, Ry Cooder, and the list goes on. Parks even helped Frank Sinatra overcome adversity.

“I was at Warner Brothers,” Parks says. “I was an office boy. Why would it be that the head of Warner Brothers would want me to go have lunch with Frank Sinatra to persuade him to stay in the record business? Why would I be that guy? You got me. I told him, ‘You can’t quit Mr. Sinatra. You’ve spanned presidencies. Don’t let these Beatles kick you around. You can handle this.’ Mr. Sinatra said, ‘Thanks, kid. I’ve learned a lot.’ And my brother [Clarence Carson Parks] wrote that [1967] tune for him [and daughter Nancy] called ‘Somethin’ Stupid’ which became a one trick pony and the Energizer battery that just kept going.”

Parks has also taken to helping younger artists, some unexpected like nineties rockers Silverchair, the Daniel Johns fronted Australian group who Parks worked with on their 2007 grunge departure, Young Modern. Parks has also joined forces with New Zealand singer-songwriter Kimbra, American dubstep pioneer Skrillex, while his most recent effort, 2019’s ¡Spangled! is a collaboration with Guatemalan singer-songwriter and Latin Grammy Award winner Gabby Moreno that celebrates the migration of song across the Americas. In 2008, Parks teamed up with Los Angeles based singer-songwriter, Inara George, one half the indie pop duo the Bird and the Bee, and daughter of Parks’ friend and Little Feat front man, the late Lowell George.

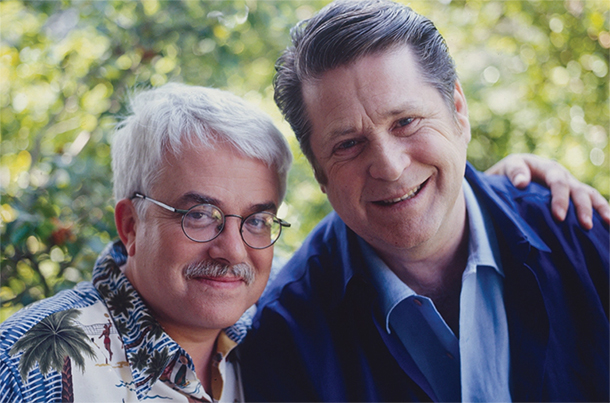

Van Dyke Parks and Inara George. Photo by Roman Cho.

“Van Dyke is kind, generous, and thoughtful,” George says. “And what he does with orchestrations, really changes the structure [of a song]. He’s such an individual and has a specific perspective. My intention was that I never wanted to tell him what it should be. Van Dyke has his own unique sound that he brings to whatever he touches. I didn’t want to interfere with that. I just wanted it to be more of a collaboration than me bringing someone in to work on my record. It was more about making something that was ours. Van Dyke will take a lyric and give it a flourish by bringing in a reference that I couldn’t tell you intuitively. That’s one of his gifts. He’s this insane musicologist. He knows music and the origins. If you listen to the music, there’s just so much that he brings to it. It’s fascinating. When you’re at a studio, and Van Dyke has created these beautiful orchestrations and then you hear the musicians doing it, they are challenged. These all-star orchestral players. He pushes them to their limit. I don’t think there’s anything that can top that. It’s really exciting and cool.”

“They think that arranging is unnecessary,” Parks says. “This is how I got three kids through college. That, and the fierce loyalty of my wife [Sally]. We’ve been married forty-one years. You have to look at the big picture. Everybody gets complicated with this diversion into music and its genres, which is a man-made definition that is conceded and intolerant. The tendency is for these rock-Nazis to pull what they do. Pull rank with what they call serious music. Classical.”

Parks certainly plays music many consider serious, but he’s not stuffy. Not in music, and not in life. Exhibit A – the back cover of his 1989 cross-cultural effort Tokyo Rose. The album, which features friend Danny Hutton of Three Dog Night on guest vocals (“Yankee Go Home”), is Parks’ musical take on Japanese-American relations, and subsequent eighties trade war. Serious subject, yet Parks appears in a cartoonish sailor outfit, jovially posed as his prop rowboat sinks by the tail of a wale. Parks contrasts the scene he’s created with the front cover – an image of a powerful Japanese woman harpooning the wale. He’s not trying to look cool. He makes a statement at his own expense. There is this same balance in his music and life.

“Van Dyke is hilarious,” George says. “He has this one liner when we’re at rehearsal, ‘I’m going to the men’s room to see if I qualify.’ Then he gives out these cards. The top line is, ‘Mr. Van Dyke Parks apologizes for his behavior on the night of ____.’ It’s blank [for him to fill out]. Then it says, ‘And sincerely regrets any damage or inconvenience he may have caused.’ Then it gives his information. He’s very fun and entertaining.”

“There’s this tremendous border between what’s on the street and what we think is elite,” Parks continues. “I have somehow tried to take advantage and celebrate the qualities in both areas. That is extemporaneous stuff. The big bang, the toe tapping groove, and the ability to… I don’t want to use a big word…. annunciate it. That’s why I use string sections. String sections have the big boogie. It’s two worlds, highbrow and lowbrow. People are still messing with it, and using phrases like something being ‘quirky.'”

“Quirky? What does that word even tell anyone?”

“Nothing.”

“No. It doesn’t. I don’t use that word.”

Trying to define Parks using one word is about utilitarian as Mike Love dissecting his lyrics. Not at all. There’s no defining someone so singular.

“I think there’s a sullen residue,” Park continues, “from the maverick cowboy, the faux cowboys of the Bob Dylan era. And I am a fan of Bob Dylan. I am an absolute fan of a man who stays interested and doesn’t attempt to be interesting. But there is a group of camp followers, from the Eagles to the lower altitudes with this cowboy consciousness and rhinestone cowboy hangover that inflicts movies. Clint Eastwood is machismo rock and roll, and I found it tremendously upsetting.”

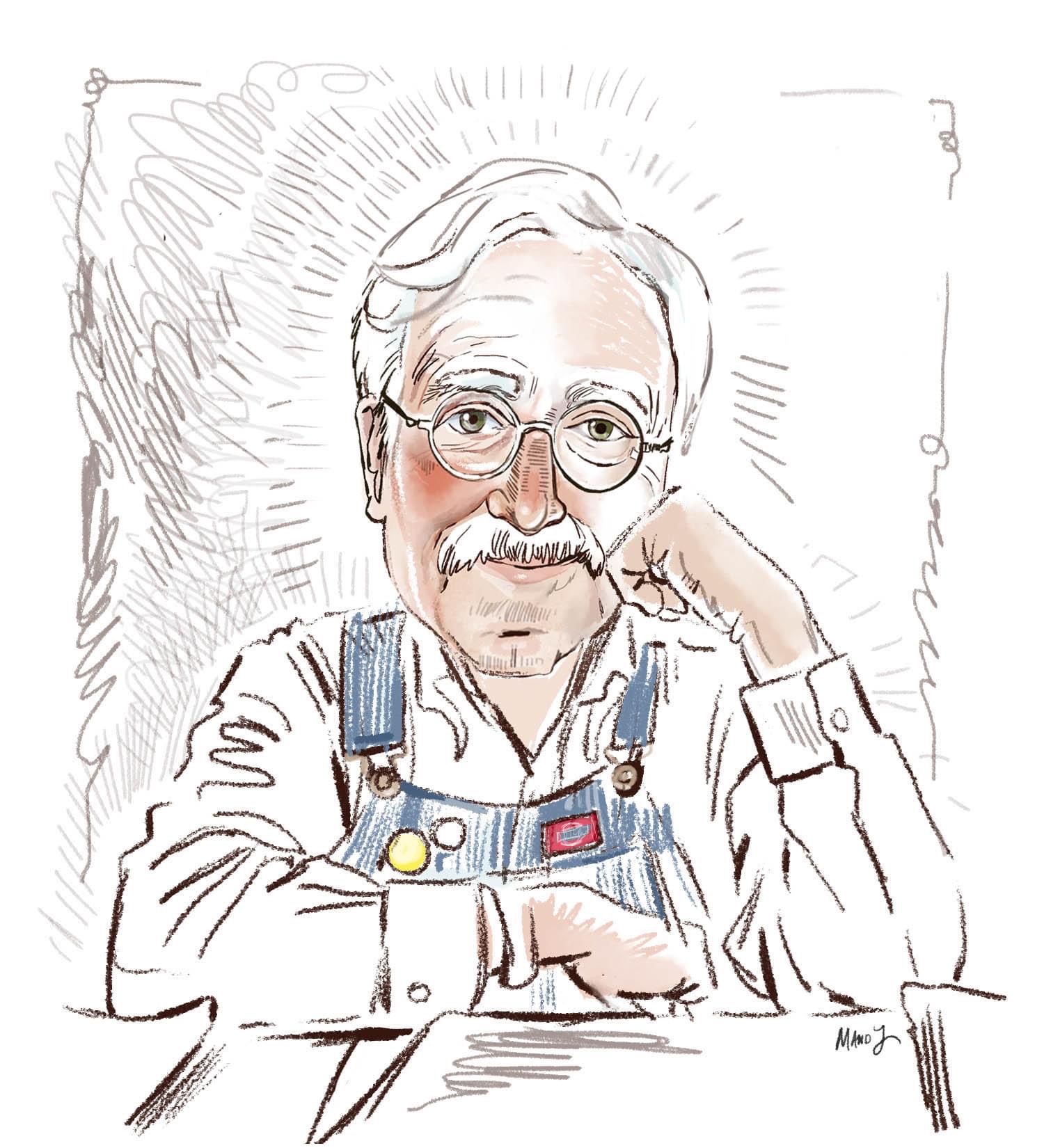

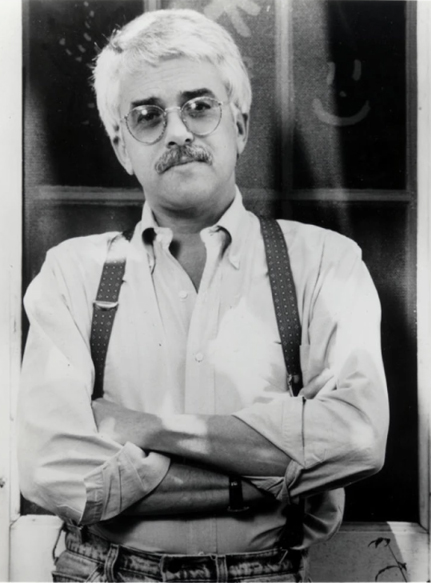

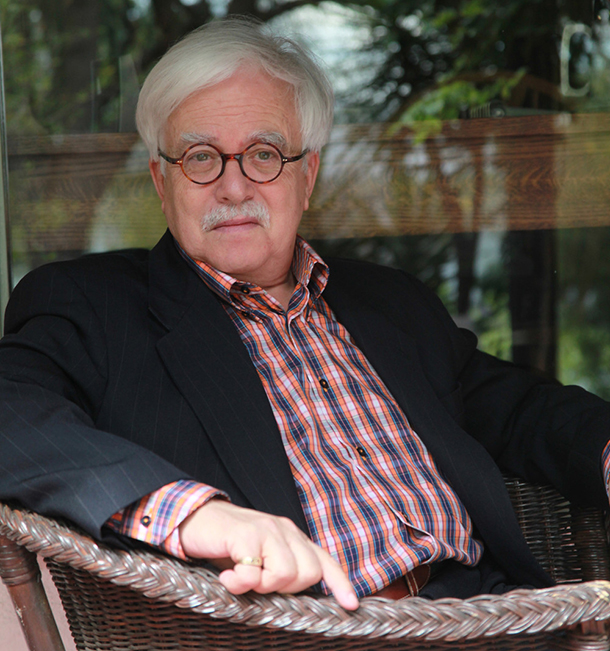

Parks is not macho of faux cowboy. and authentically captures the American landscape. Currently seated next to a black Steinway piano with white hair and mustache, Parks recalls Mark Twain. Southern dandy deluxe with a Yankeness at once. Then there’s the semi-rimless glasses, and overalls paired with a pink button-down shirt. Very Oxfordian intellectual of the Mississippi variety. Matches his Faulkner-sized vocabulary.

“Tell me about your early days in Mississippi.”

“My mother was a Methodist and my father was a Presbyterian,” Parks says. “My father was in [the second] World War when I was born. I was two, and he was the Chief Psychiatric Examining Officer at the liberation of Dachau and Auschwitz.”

“Wow.”

“Yeah. So, he was gone, and I was with my mother. Two things I remember about Mississippi, this primary youth. First, the pine trees. You memorize the trees. That’s what you’re doing in life. That’s what it’s all about. It’s the trees you remember. The naturalist authors informed my youth. This is the spine of my American literary experience. Look at [Henry David] Thoreau. The man [who] invented the expression ‘civil disobedience.’ You may think the guy might be a little light in the loafers. No. He was tall as timber. Understood and stood up.”

As Thoreau once said, “I took a walk in the woods and came out taller than the trees.”

“It’s the books you’ve read that you remember,” Parks continues. “‘How To Take Out a Tick,’ for example. Counterclockwise. I remember when the Steinway came into our family. This piano [I’m sitting at]. It’s been in our family for one hundred and one years. My brothers and I made a fort out of the box when it came.

Parks circa 1989. Warner Brothers promotional shot by Carl Studna.

“I [also] remember when Mr. Wells came into the house. My mother was cooking [in] the kitchen where the family gathered. Mr. Wells was rattling a glass with ice. He said to my mother, ‘We just burned a cross on Mrs. Goldstein’s lawn.’ My mother turned around immediately and said, ‘Get out of this house and never return.’ It did not escape our mother’s attention that Mr. Wells was the president of the bank and held a mortgage on our house. So, I think that should give you an idea the kind of family I was with. A mother that did not delay justice a moment. I’m so happy she is not around to watch Mitch McConnell defend what is left of the Anglo-American. It just isn’t funny.” Parks pauses and takes a sip of a brown drink he has in a glass. Looks like iced tea with a mint leaf floating at the top. “So,” he continues, “I fled Mississippi, and I brooded.”

“But I am a member of the Mississippi Musicians Hall of Fame,” he continues. “I followed the daughter of my favorite blues singer, Howlin’ Wolf, to accept an award. I’m sitting there with my wife in [my hometown of] Hattiesburg where I don’t know one person with a house. It was very sad for me. My wife and I were in a hotel room sobbing about the hearts we left behind in Mississippi. Howlin’ Wolf’s daughter got up there, and held this little wooden flame with faux bronze [award], and she broke down. ‘My daddy would walk a mile for a spoonful of just something to eat. You’re too late,’ she sobbed. My wife held my arm as I attempted to rise, and said, ‘Keep it light.'”

“Man. That’s heavy.”

“That’s Mississippi,” he says. “I’ve been back and forth many times. My career in music took me [on the road] with a steel band.” Parks points his phone at a picture of two buses side by side. “That’s a picture of my friends. There’s twenty-eight men there.”

“Oh, cool! Discover America!” I say with excitement as the buses are the ones featured on the cover of Parks’ 1972 calypso heavy sophomore effort. His friends, the Trinidad Tripoli Steel Band who he first worked with in 1971, acting as producer on their Grammy Award nominated Warner Brothers effort, Esso.

“[The band and I] went in those buses,” he continues. “I was attempting to feed them. I was making $285 a week. It took everything that I had in my power at Warner Brothers to get those men fed. I went through the Southern United States when the bus broke down and crashed. I tasted what America was all about. I wasn’t flying over any state. I was driving through. That’s when I discovered America. That’s what gave me the concept [of] a bus that went from Trinidad to Los Angeles. I didn’t make up anything.”

“When did you first get into calypso?”

“When did you first get into calypso?”

“I can’t tell you when I first heard it, but my uncle would have brought calypso into our family. In the golden age of analog, my parents had calypso recordings on the Magnavox. Rum and Coca-Cola. My mother’s favorite drink. It was in the blood. South of the border. The Tropicana.”

Parks plays the piano. It’s good he’s seated next to one. He communicates through music like jazz musicians do. Notes are linguistic.

“That’s Cuban, 1857,” he informs.

“I dig it!”

“I was aware of this music because I played piano all my life. It went everywhere. It was transoceanic. I’ve always appreciated the Southern zephyrs. I’ve seen a lot of slush, a lot of sullen Aprils where it didn’t get warm quick enough and stayed sullen. To lighten up, I see a more Southern meridian.

The music that first took me south was [Louis Moreau] Gottschalk of Louisiana. New Orleans is the gateway for any Pan-American Caribana association. It’s the gateway to the Caribbean. To South America.”

“So, dig,” he continues. “All kinds of music makes an impression on me. I went to boarding school in Princeton, New Jersey. I’m learning music every day. From Cole Porter to Fats Waller who was on my parents’ record player. That was the best. Then the boys would bring in things like Little Richard. I remember and when Les Paul came out with ‘Lover’ [in 1948]. [Paul’s 1951 collaboration with Mary Ford on the jazz standard], ‘How High the Moon’ got me excited about recording at an early age. And I remember the day [Bill Hailey and the Comets] ‘Rock Around the Clock’ came out [in 1955].

“I had a fantastic life. I got to meet [former Illinois Governor and United Nations Ambassador] Adlai Stevenson on a campaign stop because I went to a private boy choir school on two-hundred-fifty acres. Sassafras roots, arrowheads, and frog legs. The headmaster’s wife loved them. And she’d pay fifty cents for some frog legs. We took the lamp out [the cement ship] and whack! Great life. I met Albert Einstein. Sang carols in his kitchen for over an hour. I can prove it with corroboration.”

“I believe you.”

“There’s Lowell George holding a gravestone,” he says, pointing at a picture on his wall. “He’s at a cemetery in Cockeysville, Maryland. He was laughing because it was the Parks section of the graveyard, like, ‘I’ll outlive you.'” Parks raises his hands to the sky. “I’ve outlived Lowell,” he says with exasperation. “We wrote a song or two together,” he continues, “and at a major point in my life I can fairly say I was his best friend as he was mine.”

“I was born in Maryland,” says Inara George. “They moved the family out, and Van Dyke was there when I was born. My dad died in [1979] just before my fifth birthday. But my mother kept Van Dyke in our lives. I always enjoyed being at the house, hearing music, and hearing him talk about the garden. He’s an amazing cook, and his wife Sally is great in the garden. But I think he does really well there too.”

“I’m gonna be ’round my vegetables. I’m gonna chow down my vegetables. I love you most of all, my favorite vega-table,” as the lyrics go.

“Lowell understood the art of cliché,” Parks continues. “He understood that it could be an art.”

For the past decade, my area of focus has been Texas music, so my introduction to Lowell George and Little Feat came by way of their 1977 cover of Terry Allen’s absurd take on the adventures of Jesse James, “New Delhi Freight Train.” I believe Allen and Parks are akin in some ways. Both are masters of wordplay, use unconventional sentence structures, impart theatrical techniques, capture scenes of the American west, cover cross-cultural topics, and shine in their unapologetic individualism. These are not your run of the mill songwriters. Lowell George demonstrated through his work, and appreciation of the work of others, that he was hip to that which most are not. He simply got it.

“Lowell was a pop artist,” Parks continues. “But Howlin’ Wolf was his favorite blues artist. He would have spun in his grave knowing I got an award the same night as his hero Howlin’ Wolf. But you get to a point in life where you realize half the people you know are dead. I’m very much interested in that aspect of every one of the peerages that I have. I’m interested to see how everyone’s breaking flight formation and veering off. Some with a sputtering engine. I’m studying this, and it’s incredible to see whose survived and whose still rehearsing old victories. I’m not sure whether I should be doing that at my age.” Parks pauses and takes a sip of his drink. “Is this interview going well?”

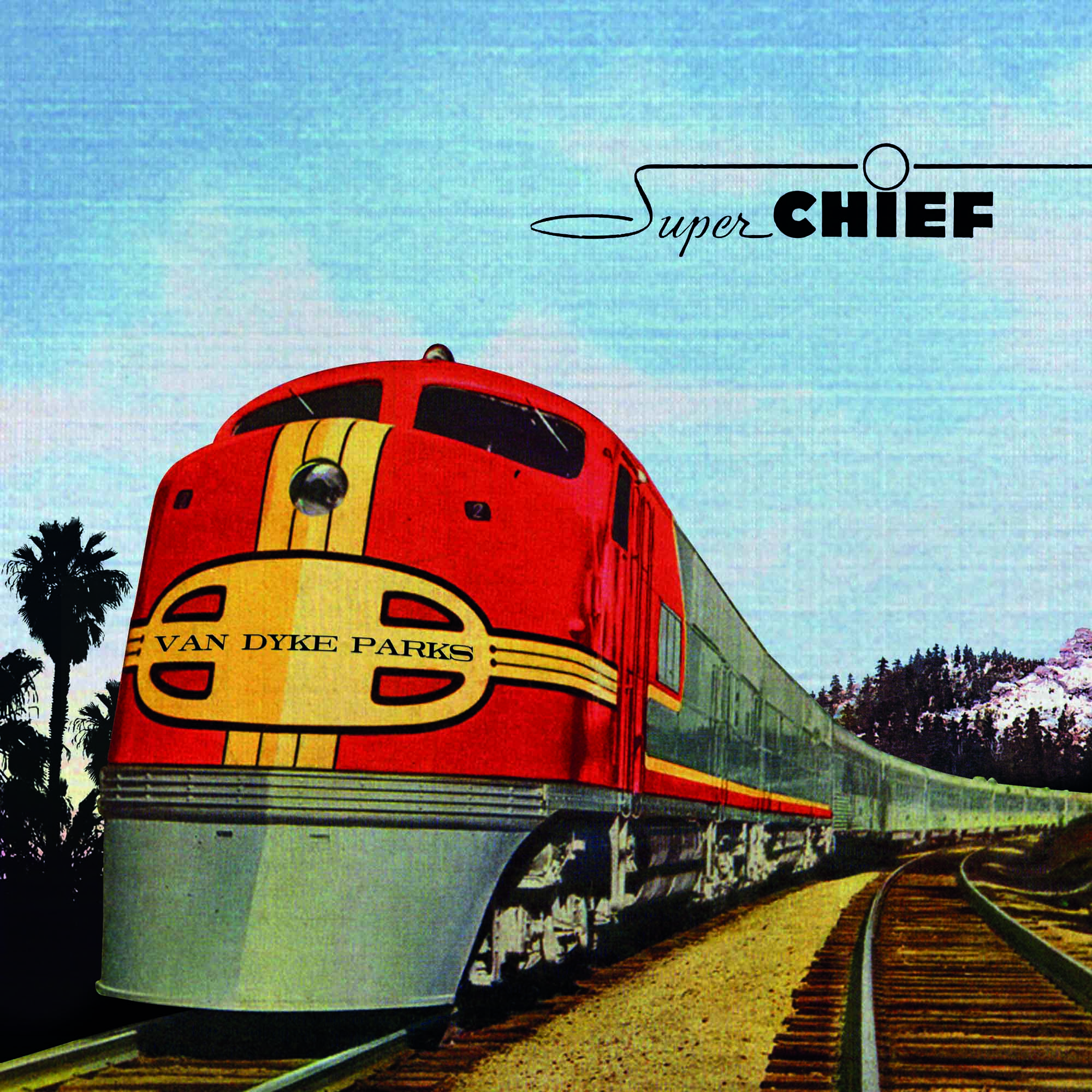

“It’s going great,” I say. I’m not here to interrogate him. “Tell me about your first trip out to California on the Super Chief.”

“First of all, I know this,” Parks says. “The best night’s sleep you will ever get is on a Pullman [railcar], because it’s rocking you to sleep. And there’s always something to grab onto if you’re on your way from the bar. Always something to keep a functioning alcoholic in the aisles. The whole thing is just padded luxury, and 360-degrees of incredible continent.”

This is no Tom Joad or Kit Carson tale. Parks took the trip out West as a child actor to appear alongside Grace Kelly and Alec Guinness in the 1956 film the Swan. In 2013, Parks transformed his adventure into the fantastical orchestral effort, Super Chief: Music for the Silver Screen.

“We went from Princeton Junction to Chicago on the Pennsylvania Railroad,” he continues. “Then, I trunked with my mother across the prairies. The great grasslands, massive beyond reckoning. It took me three days to get across the United States at a clip, and that was with plenty of time to stop and meet the Indians in Albuquerque, and really get a sense of it through their art. I was astonished [by] the rugs they would weave that were supposed to be for the delight of the bourgeois American public [who] would put them in their garden houses, maybe. These beautiful fabrics woven by the Navajos. And the Hopi jewelry. Amazing design and cultural impact. It made an impression on me. And California did. We got off the train in Pasadena. I said, ‘Mom, did they run out of money?’ I thought [that’s why] we couldn’t get to Los Angeles. But the head of MGM insisted that none of his stars get off the train in Los Angeles. So, we got off in Pasadena. Then, I was driven by a stretch Cadillac limousine to the Chateau Marmot at 8221 Sunset Boulevard. That’s where I stayed. That was 1955,” Parks pauses. “I think it’s very important that you know this. Very important to the interview.”

“We went from Princeton Junction to Chicago on the Pennsylvania Railroad,” he continues. “Then, I trunked with my mother across the prairies. The great grasslands, massive beyond reckoning. It took me three days to get across the United States at a clip, and that was with plenty of time to stop and meet the Indians in Albuquerque, and really get a sense of it through their art. I was astonished [by] the rugs they would weave that were supposed to be for the delight of the bourgeois American public [who] would put them in their garden houses, maybe. These beautiful fabrics woven by the Navajos. And the Hopi jewelry. Amazing design and cultural impact. It made an impression on me. And California did. We got off the train in Pasadena. I said, ‘Mom, did they run out of money?’ I thought [that’s why] we couldn’t get to Los Angeles. But the head of MGM insisted that none of his stars get off the train in Los Angeles. So, we got off in Pasadena. Then, I was driven by a stretch Cadillac limousine to the Chateau Marmot at 8221 Sunset Boulevard. That’s where I stayed. That was 1955,” Parks pauses. “I think it’s very important that you know this. Very important to the interview.”

Very important? I brace myself.

“In 1955,” he continues, “[the] Swanson [brothers came out with] frozen beef pot pies.”

Beef pot pies. Not surprising Parks finds the advent of the frozen beef pot pie of historical significance. It is a marker. Just watch the six-hour docuseries, The Food that Built America on the History Channel, and it’s evident the food industry had a massive impact on the development of American industry. By the end of the nineteenth century, it was one third of the United States economy. Frozen food was revolutionary from the time Clarence Birdseye perfected flash freezing in 1924. Food that doesn’t spoil and stays fresh. It changed our culture beyond culinary.

“It was a new thing. It was the first frozen instant meal,” Parks continues. “Everybody was amazed. It was in supermarkets, put there marginally by the ice cream section, soon to get its own section. I got some right on their first issue in Los Angeles. I made one and took it across the hall to Eartha Kit. She greeted me. This beautiful, incredible woman. Amazing. Tremendously sexual presence. She was in a peignoir. Behind her was a butterfly screen. Which made it more exotic. I was twelve and completely baffled.”

“Wow.”

“So, I came back to Los Angeles in 1957 to be in a musical called Fanny. That was by car, and rugged. We had a 1956 Ford station wagon with air conditioning, which was a luxury. It was in its trial runs with the automotive industry. If you see these old pictures of Route 66, there’s cars with a contraption outside the driver side. They called those things the Swamp cooler. It was a rustic adventure, getting baked in the sun, just this side of an emergency room and dermatologist. But I learned the United States. The south that was pre-air conditioning. These eras are benchmarks of my life and understanding.

“In 1963, I came out to California [again] with my brother. I played Reno with [sixties folk group] the Brandywine Singers as a guitarist. That was an amazing. Hanging around with gamblers and falling in love with dealers. Then getting my first song, ‘High Coin’ picked up by a group called the Charlatans. I met them after playing Harrah’s. I went Virginia City [Nevada]. It’s a ghost town, an active ghost town. Lost its population. Threadbare. There’s a couple of saloons, and in one of them is the Charlatans. They were hippy-delic people in a purple haze. When I walked in with my big bass player [they said], ‘New York City!’ They thought they nailed me because I was a preppy. Button down. I said, ‘Do you mind if I do a set?’ There were two or three people just drinking at tables, maybe thinking of something, and staring at nothing. They said, ‘Sure. Be my guest.’ Immediately they melted and asked if they could record the damn song. They did, and it became a big hit in San Francisco [in 1969].

“That’s why Jefferson Airplane asked me to produced them. They scared the hell out of me. When they were too high to eat, I knew they were too high to handle. That’s where I draw the line. I turned them down, and turned them onto my friend Rick Jarrard. He produced them. The first thing they did was put LSD in his coffee. I can honestly say at this stage of my life, I’m just as happy about what I haven’t done,” he pauses. “Why are we having an interview? Do we know yet?”

“Well, technically we’re talking because you re-released Orange Crate Art,” I say. Parks has had every opportunity to push a project and has not done so at all. “But really,” I confess, “I’m between books, and always wanted to write a feature on you. We’re just here to talk your life and work. Whatever you want.”

“It’s very kind of you to take notice.”

I first took notice in 1998 as a fourteen-year-old living in rural Western New York, next door to a cornfield and down a few houses from some cows. I hated anything rootsy, because I was getting bullied for being a preppy. Then, I heard some tracks from Smile on the Good Vibrations Box Set, one of the few places to hear the tracks nearly fifteen years prior to the release of the Beach Boys SMiLE Sessions. I was blown away by Parks’ lyrics. “Over and over the crow cries uncover the cornfield.” Suddenly, I was seeing images in music, images that surrounded me. It wasn’t just someone singing about emotions. That same year, I got a copy of Domenic Priore’s Smile era scrapbook, Look! Listen! Vibrate! Smile! I saw an original 1967 Warner Brothers advertisement for Song Cycle. It had the album cover outlined in framed filigree. Parks was so scholarly in glasses and loafers. Someone to relate to. Then, over top Parks’ picture, it read in trippy-delic font, You Are About To Become Involved With Van Dyke Parks! I was a kid, and thought, Woah! What does that mean?

Shortly thereafter, I heard Song Cycle and it changed my musical trajectory. All of Parks’ work did. It opened my mind. Taught me things. To pay attention to words. I thought he was so clever to wordplay “juxtaposed / just suppose” as he does in “Palm Desert.” And I was a history nerd. So it was all there.

Parks’ music also gave me an early awareness of the importance of song preservation. Twenty-two years later, I just finished a book for Texas A&M University Press, Live Forever: The Songwriting Legacy of Billy Joe Shaver, the point of which is to aid in the preservation of Shaver’s songs and legacy. Parks consistently demonstrates the urgency of songs being passed down through generation by re-imagining them. I saw “Public Domain” on Song Cycle, and looked up what it meant. I learned copyright history from that clever reversal of song title and credits that would later inform my research as a philosophy major in college. And I am related to Stephen Foster. I grew up on his music, but did not come to appreciate it until Parks. Foster, who died penniless because of lack of copyright in songwriting, making money only off the sale of sheet music. It’s like Spotify today. In 2014, Parks even wrote an op-ed in the Daily Beast, Van Dyke Parks on How Songwriters Are Getting Screwed in the Digital Age.

It’s amazing how he presents history objectively, yet persuasively, and always presently. I was a freshman in high school and blown away. Then, a teacher gave me a tape of Orange Crate Art. I took it with me to Florida on a trip to visit my grandparents. I discovered they weren’t well, and was upset. I put on my headphones, looked at the palm trees, and I felt like I was in California. Orange Crate Art got me through a tough time. It’s amazing, the power of the arts and how they inform our own work and development.

“2011,” I start. “I saw you play in Thousand Oaks. I was there with my copy of Song Cycle for you to sign,” I admit. “I handed you the record, and you said, ‘I made all of my mistakes on this first one.’ What did you mean? What do you think of the album?”

“I think it’s great,” Parks says to relief. “It’s a wonderful piece of work. I had no argument with it. I didn’t know how to make a record. I think that showed. I couldn’t quite conceive that people would listen to it. I never imagined that it would be reviewed or figured out or not figured out. I just thought I’d get away with it. I’d heard a lot of records of different kinds of music, and I thought everything I was doing was absolutely legitimate. It expanded the knowledge of what to do in a studio and a studio’s potential in the age of analog recording.”

“For example, the marimba part I had in mind for [Donvoan Lietche’s] ‘Donovan’s Colors’ required repetition. I didn’t have the ability to revolve the notes. So, I’m quite empirically checking it out. It turns out, if you take a 15-ips [speed] tape and play it at half speed, you reach an octave. When I learned that, it was a eureka moment in my life. Of physical sciences converging in such a wonderful way that I could play the marimba part in half-speed and come out sounding like I could actually play it. Isn’t that something? You learn things. Song Cycle taught me things. But sometimes I listen to it, and it embarrasses me. They all do from time to time. I wish that I had not let something go. You don’t have to be a Randy Newman to have certain misgivings for what you’ve done. There’s good reason for wondering. My favorite line from my wife is, ‘Whatever was I thinking?’ She’s from Memphis. She told me there’s two things a southern gentleman should learn to say, ‘Yes, mam,’ and ‘Whatever was I thinking?’ So, when I look at an album, I generally say, ‘What the hell is going on here?’ But once I drop that egotistical concern for survival,” he pauses, and thinks. “Because,” he continues, “I’ve had every insult that could possibly leveled on every occasion of an album release.”

Out the gate, Song Cycle was attacked because it failed to be the commercial success Warner Brothers hyped and hoped for. By no fault of Parks. At the time he was working with pop melody master Wilson on Smile, so they incorrectly assumed he would be the mainstream success the Beach Boys were. When that didn’t happen, the label tactlessly took out an ad about their own failure at Parks’ expense. The headline read, How we lost $35,509.50 on “The Album of the Year.” (Dammit).

“I decided not to begrudge the jealous executive who was so cute, and possibly bring the honor of being sold for a cent so that people would pay attention to me,” Parks says. “[Warner Brothers] made a great deal of money with it, me, and the music that I generated there. That’s a fact. Totally black ink operation. Just not boys with promotion. Men with twenty-dollar bills in brown bags just didn’t know how to deal with it. In an age of college FM radio, they didn’t know what to do with it, or Randy Newman, or any of the succeeding acts that I worked on.”

Song Cycle opens up with a forty-five second clip of Steve Young [Heartworn Highways] singing the seventeenth century ballad “Black Jack Davy” through a cloud of Appalachian picking. Parks made Young sounds like a recording from a bygone era. It’s the perfect segue into Randy Newman’s “Vine Street,” as it begins, “That’s the tape that we made. But I’m sad to say it never made the grade.” Newman wrote the song for Parks. Parks elevated the work to another level through his execution.

Song Cycle opens up with a forty-five second clip of Steve Young [Heartworn Highways] singing the seventeenth century ballad “Black Jack Davy” through a cloud of Appalachian picking. Parks made Young sounds like a recording from a bygone era. It’s the perfect segue into Randy Newman’s “Vine Street,” as it begins, “That’s the tape that we made. But I’m sad to say it never made the grade.” Newman wrote the song for Parks. Parks elevated the work to another level through his execution.

“Randy had a good job and proven track record as a songwriter,” Parks says. “I wanted a real song. Something to stabilize [Song Cycle]. It was somewhat biographical, because I did live on Vine Street [in Hollywood] where my wife made perfume at the back of the room.”

Parks begins to play Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, singing “Vine Street” over top.

“Wow, cool. I never knew that.”

“Yeah. So, dig. You hear this folk song ‘Ode To Joy’ which has to do with brotherly love in an age of civil strife in Selma. Clever of Randy Newman to do that. It gave the record a sense of place and gave me a chance to focus on my personal problems, and dilemmas that I tried to get through. My brother [Benjamin’s] death in 1963, and that of John Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr. It was a tumultuous time, and a lot of drugs. I had probably as much as a person could have in the way of a constant and affectionate regard for the practicality of Marijuana in the creative process, and it shows. After Song Cycle, I would say I found my escape from freedom in Discover America.”

Through his work, Parks has often dealt with topics of prejudice, xenophobia and the slaughter of indigenous Americans. But “The All Golden,” from Song Cycle deals with another type of prejudice, that towards the poor southerner, as the song is a divergence of cultures that follows the story of an Alabama-to-Los Angeles transplant. He’s an open-minded bohemian judged for his southern affiliations in the era of progress. “You will know why hayseeds go back to the country,” as the lyrics go.

“When I met Steve Young,” Parks says, “I had my apartment at 72, 22 1/2 Melrose [Avenue] in Los Angeles. Now a trendy place. It wasn’t then. I met Steve [nearby] at the Troubadour [in West Hollywood]. His apartment was over on Mariposa Boulevard [in East Hollywood] in a place they called Tobacco Road, a bungalow with guys from Alabama on both sides of these little apartments. I loved Steve because he had a picture on his wall of the detestable governor of Alabama, George Wallace, with a Hitlerian mustache. He hated Wallace. Steve felt like I did – a little embarrassed that he’d ever been near Mississippi, or Alabama or anywhere, because there was a hex on it. He is one of the few people I knew who had to pick cotton as children because they were so poor. So he had a lot of issues, anger. He typified the outlaw cowboy, that thing Waylon Jennings did. Waylon wanted to be Steve Young [who wrote Jennings’ “Lonesome, Ornery and Mean”]. Because your scars are your beauty marks. This is who you are. Steve was so scarred.”

“I felt such a great empathy and love for him. They weren’t treating him with respect in the record racket. Anytime I see somebody go down I try to pick them up. I did that for Brian Wilson [with Orange Crate Art], just as he’d picked me up. Just in the moment. Somebody else would have come along.” Parks also picked Wilson up in the early seventies, bringing him the start of “Sail On, Sailor” at a time when the Beach Boys were struggling to stay relevant. The song became the lead single on the Beach Boys 1973 album, Holland.

“So, Steve Young, man of mystery,” Parks continues. “I just heard some desperate call he was lost at an airport without a wallet. I wasn’t there to answer my phone and there was no way for me to return the call. The next thing I knew, he was dead.”

“Wow. Man. That’s heavy.”

“Yeah.”

“So if you look back at your early recordings like ‘Come To The Sunshine,’ you had mandolin…”

“I had mandolin, mandola, and mandocello, with a twelve-string guitar over-layed by Tommy Tedesco [of the Wrecking Crew],” he says.

“I discovered your music from Brian Wilson. I was first hearing roots instruments because of you. Now I think back to ‘Cabin Essence.’ That was the first time I was hearing a banjo in popular music. Was that your influence?”

“I think so,” Parks says. “The banjo makes an art of cliché. It’s the identifying sound of the simple life. Rustication. There are two kinds of banjo playing: clawhammer, and Scruggs. But you can also use them in this single plectrum, which is totally Squaresville. It’s about as gauche as it gets. ‘Droit gauche’ is what Lowell George and I used to call it. The right to gauche out. A super honky approach. That’s what the banjo in ‘Cabin Essence’ is doing. This is how important these instruments are, they find a prominence in a generation. Then they’re vestigial organs that get whipped aside, and you lose all that it suggests if you abandon. That’s why I like to use those things. It’s like food. We’re Americans. What do we love? We love wild rice, don’t we? Isn’t it one of those essential foods? How about pecans? Think mighty Mississippi. Think river bottom. Trees that can produce this great nut. American. Take your potato, your corn, and take the cranberry. For Pete sake, these are typical American things and these ingredients wind up on menus for American food.

“You notice on Orange Crate Art, there’s a presence of [harmonica player] Tommy Morgan. I salute him. He played the ‘Sakura (Cherry Blossom)’ for the Empress of Japan as a moment of entrant in the reconciliation of the cultures. The defeated emperor and his wife. Tommy Morgan played his harmonica for them right after Hiroshima [in 1945]. Tommy Morgan was there on the front lines across the Pacific Rim. This is the power of forgiveness in action. Tommy Morgan had played his way through the theme songs of all the great cowboy western movies and television shows. Tommy Morgan was all over the place, and with Toots Thielemans, arguably the greatest harmonica player alive. He’s now lost his lip. He had a stroke and gave all of his harmonicas to a guy named John Kip. Why? Because the harmonica is a very intimate, close-range instrument. Where did I meet him? Brian Wilson. Tommy Morgan went on to decorate the work of Brian Wilson. Bass harmonica. This man brought such an incredible close-range intimacy. You can carry on a normal conversation with this music, and that brought stability and high society to Brian Wilson when he least wanted to go into a studio. I brought his old friend Tommy to bring things into focus, and to show Brian that I had learned a lot from him. That I was employing as much as I could of his signature in the work. That’s what I did.”

“You notice on Orange Crate Art, there’s a presence of [harmonica player] Tommy Morgan. I salute him. He played the ‘Sakura (Cherry Blossom)’ for the Empress of Japan as a moment of entrant in the reconciliation of the cultures. The defeated emperor and his wife. Tommy Morgan played his harmonica for them right after Hiroshima [in 1945]. Tommy Morgan was there on the front lines across the Pacific Rim. This is the power of forgiveness in action. Tommy Morgan had played his way through the theme songs of all the great cowboy western movies and television shows. Tommy Morgan was all over the place, and with Toots Thielemans, arguably the greatest harmonica player alive. He’s now lost his lip. He had a stroke and gave all of his harmonicas to a guy named John Kip. Why? Because the harmonica is a very intimate, close-range instrument. Where did I meet him? Brian Wilson. Tommy Morgan went on to decorate the work of Brian Wilson. Bass harmonica. This man brought such an incredible close-range intimacy. You can carry on a normal conversation with this music, and that brought stability and high society to Brian Wilson when he least wanted to go into a studio. I brought his old friend Tommy to bring things into focus, and to show Brian that I had learned a lot from him. That I was employing as much as I could of his signature in the work. That’s what I did.”

A few years after Orange Crate Art, Parks went on to arrange Wilson’s 2000 Pet Sounds Symphonic Tour with Paul Mertens. I saw it in Cleveland in 2000 at age fifteen, and in all times I have seen Brian Wilson, never did the album sound so beautiful as that evening. Then, in 2004, Parks worked with Wilson and his bandleader extraordinaire, Darian Sahanaja to complete Smile as Brian Wilson Presents Smile, first as a live orchestral work to debut in London. I flew to London from New York, took the train and to Liverpool to see it a few days later. I was nineteen and blown away. This album that was supposed to top Pet Sounds, but never came out while the Beatles release the psychedelic circus that is Sgt. Pepper.

It must have been difficult to walk away from the gig, but Parks was attacked, and Wilson was struggling with mental health issues, only exasperated by his use of LSD. There’s an iconic video of Parks standing outside a Tower records in 1976. He’s very tropical in a straw hat and tank top, and sums it all up quite concisely.

“I wasn’t close enough to the other guys,” Parks says in the clip. “I was in a position to defend my lyrics. It went from ‘ding woody pearl hang-ten.’ I mean, I didn’t know that language, to like, ‘columnated ruins domino’ [from “Surf’s Up”]. Mike Love said to me one day, ‘Explain this, ‘over and over the crow cries uncover the cornfield.’ It was [from ‘Cabin Essence’] an American gothic trip that Brian and I were working on. I said, ‘I don’t know what these lyrics are all about they’re not important. Throw them away.’ And so, they did.”

“So, all the chaos that was Smile, Mike Love, forget that. What is the one moment you shared with Brian that you most fondly remember?”

“Maybe it doesn’t sound so important,” Parks begins. “But I could tell when it had gotten to him. The headwind against his liberty. I wasn’t there telling him what kind of music to make. He started with music, and then I got to say weird things after he had done the notes. He made a decision to exercise his whimsy that took cartoon consciousness to a new level. Anybody who had been to a theater and seen any animation wouldn’t get all that upset. [Smile] was Looney Tunes, as abstract as [composer and arranger] Carl Stalling.” Parks is hip to the cartoonage. His working title for Song Cycle was appropriately Looney Tunes and his first gig as an arranger was working on “The Bare Necessities” for the 1967 Disney adaptation of Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book.

“But folks who weren’t used to music that had various idioms and musical anecdotes got their knickers twisted,” he continues. “I use idiomatic music and vernacular as a conscious attempt to use what we know, but in an artful re-configuring. ‘It wasn’t ‘Help Me Rhonda.’ As a matter a fact I was totally stunned by the music, and it shows. But I put a word or syllable on everything.

[Brian and I] were both disappointed at the friction we were getting for simply doing what we thought would be within his right. I was working for Brian, not the Beach Boys. I was unnecessary to the Beach Boys. Having me on a Beach Boys record would be like having an accordion player on a deer hunt. Not necessary. I wouldn’t be down there doing the kidney punches. No. That’s not my gig. My gig is things like [suggesting] cello triplets on ‘Good Vibrations,’ which was the best thing I ever did to get a job as a lyricist – come up with a musical idea. That was the ruby slippers in that epic ‘Good Vibrations.'”

“You asked me about a moment,” Parks continues. “The moment I remember, is being in the yellow corvette convertible and [going to] the All Saints Church in Beverly Hills, a place that I would later attend in a very different state of mind, I admit. Brian had no shoes on, barefoot in Beverly Hills, and we went into the church to pray. It was his idea. We walk in there, and the church was empty. Brian got it in his mind he was going to play this beautiful organ [at the front], so he walked up and started playing it. Someone came in from the Church office, incredulous, ‘You must leave.’

“He was drawn to a refuge in the face of that terrific storm of adversity we had, and just trying to do the job without distraction. Not knowing where we were going but knowing right from wrong. And in fact, it would have turned out to be entirely different had we not lost time. What can you say about precious time? You can roux it, but I don’t nurture it like a servant to my breast. I don’t want to do that. It came out.

“I was lucky to be a part of something that seemed to matter. Leonard Bernstein [whose show Wilson appeared on playing the Parks collaboration ‘Surf’s Up’] thought it was a great fusion of that which is serious and that which is totally not serious. Nothing to get upended about. It isn’t munitions manufacturing. There’s an innocence in the effort and I’m perfectly pleased with it. It took a lot of effort. It was an athletic experience,” Parks pauses. “Maybe it doesn’t sound so important, but I could tell when it had gotten to him.”

“That’s great. Thank you.”

“Is anybody paying for this time? Do we know?” he kids.

“No, nobody,” I laugh. “So, last question. I was reading this article in Crawdaddy from 1967. You’re talking about this George Washington Brown guy like it’s another human being altogether. The writer thought it was. But you’re George Washington Brown. Were you messing with him?”

“No, I wasn’t,” Parks says. “Having seen John Kennedy get what wasn’t coming to him in 1963, I was absolutely certain that fame carried great dangers. I didn’t want to be noticed. I did not want a record contract. I wanted to get in a studio and record. That’s what it was all about. I wanted an alter ego. Another persona. I didn’t want to get lost in Van Dyke Parks.”

The 25th Anniversary reissue of Orange Crate Art is available now through Omnivore Records.

VDP on the web | therealvandykeparks.com | twitter @theVanDykeParks

Courtney S. Lennon

Latest posts by Courtney S. Lennon (see all)

- Billy Joe Shaver: August 16,1939 – October 28, 2020 - November 2, 2020

- You Are About To Become Involved With Van Dyke Parks! - July 13, 2020

- The Hero of Texas Music History - July 23, 2019