By John Kruth

While a fine picker and songwriter, Peter Rowan is probably best known for his lofty voice, whether as a solo artist or singing with Bill Monroe & the Bluegrass Boys, Old & in the Way, Muleskinner and Seatrain. His blue yodels and piercing Indian cries have sent chills racing up thousands of spines over the years, while his songwriting has made him as notorious as “Panama Red” himself. Throughout his career, Rowan’s tunes have captured our collective imaginations with moon-illuminated deserts and forests, inhabited by desperadoes, Indians and love-stricken romantics.

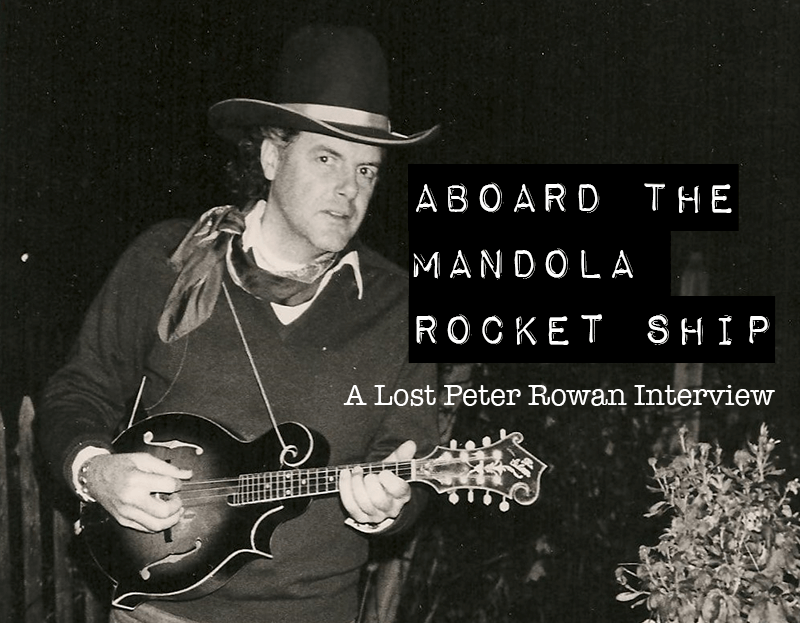

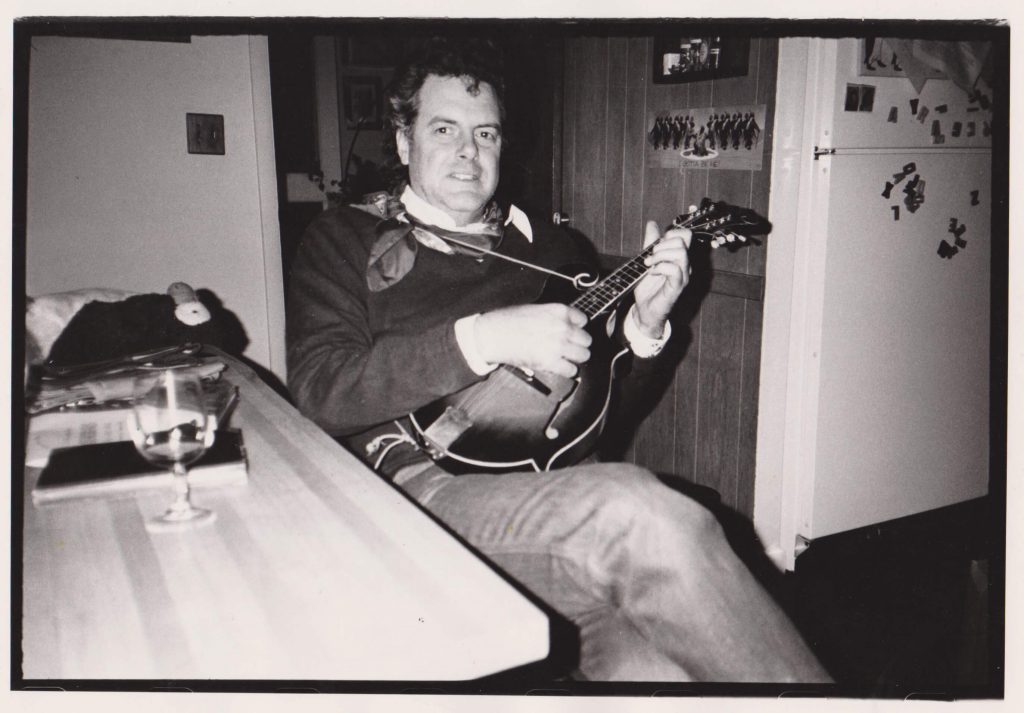

Primarily a guitarist, Rowan’s second instrument was the mandola. This was not a conscious choice on his part, it just happened to work out that way. Peter began his musical career as a mandolin picker. And although his music has gone through many stylistic changes, whether acoustic to electric – where the mandola failed to fit neatly into the scheme of things, he continued to play the instrument. The mandola has been featured on most of his solo albums. Over the years Rowan has sung with the best mandolin players of his day – David Grisman, Sam Bush, Andy Statman, Jody Stecher and the Father of Bluegrass, Bill Monroe, so he never felt the compelled to compete with that level of virtuosity. He just accompanied himself on the guitar and let the best do the rest. As he explained in this interview, he carried his mandola with him wherever he goes, (even to the Chinese restaurant where he enjoyed the Peking duck while we did this interview) and plays it with passion and a sense of wonder.

What was your musical background before joining Bill Monroe & the Bluegrass Boys?

I was playing mandolin with [Bill] Keith and [Jim] Rooney. Before I played with Bill Monroe, mandolin had been my main instrument, though I had learned guitar first. I had gotten an old Gibson mandolin and took off across the country and played it all the time. My main interest was in playing songs. I kind of had a mental block against learning fiddle tunes and doing all that fast stuff until I met Tut Taylor at the Galax Fiddler’s Convention. I stayed up all night with Tut, playing fiddle tunes like “Golden Slippers,” and “Rag Time Annie.” Galax had a different atmosphere from Union Grove, which was where I met David [Grisman]. Union Grove was a heavy-duty scene with people coming out of the mountains. It was a big contest. I always felt a little intimidated on the mandolin by the virtuosity of people like David, who was totally devoted to the instrument, so I figured that playing guitar and singing was what I was supposed to do. Before I went with Bill [Monroe] I worked with Keith and Rooney as their mandolin player ‘cause Joe Val had joined the Charles River Valley Boys.

What kind of mandolin were you playing?

A round-holed Gibson A model, a little mahogany one which I still have. Then I went to a three-point 1918 Gibson, larger bodied mandolin that cut really good. I played that with Keith and Rooney until my gig with Monroe came up and there was Bill, playing the mandolin… I mean… y’know? I always wound up playing with fiddlers and mandolin players, so I tended to be the guitar player, just try and play good, solid rhythm. I never felt that I could compete with that kind of virtuosity, so I became a singer.

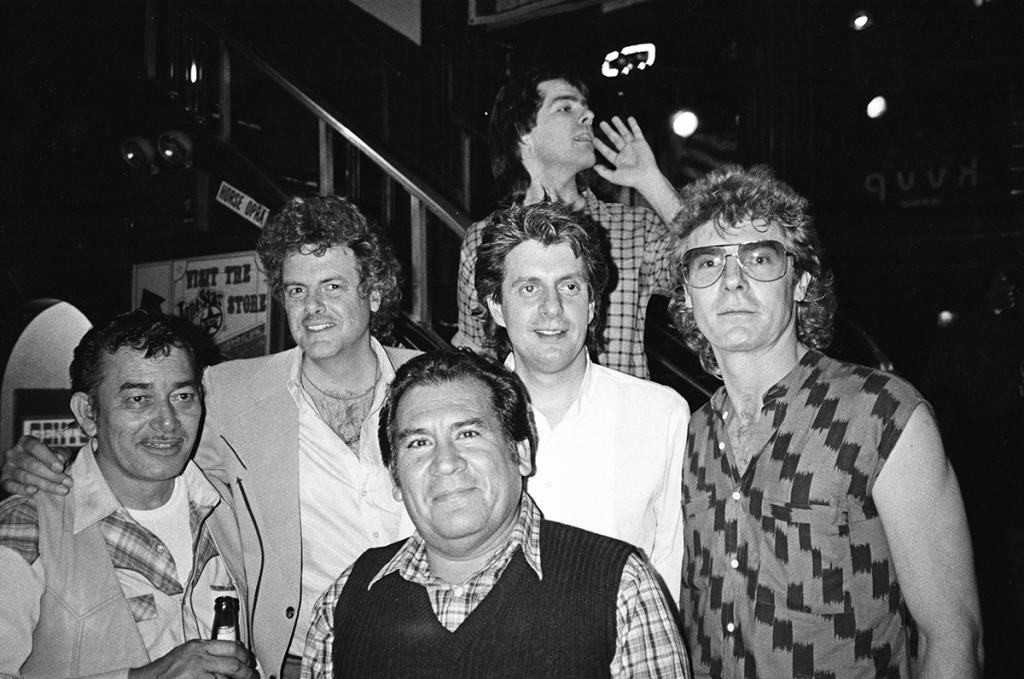

Peter Rowan with Bela Fleck, Flaco Jimenez and Sam Bush at the Lone Star Cafe, NYC.

After leaving the Blue Grass Boys, you formed Earth Opera with David and recorded a couple albums for Elektra Records.

Yeah, David had an electric Gibson mandolin and used lots of feedback and fuzztone.

In Earth Opera, you mostly played guitar and sax while David played mandolin and mandocello.

Yeah, I played tenor saxophone and David played alto.

What? Grisman played sax?!

Yeah, Richard Grando influenced us and turned us onto John Coltrane and people like that.

After Earth Opera you joined Seatrain, with Richard Greene on violin. What instruments did you play in that band?

Electric guitar. I tried to bring the mandola into it, but it was a foreign element in that conglomeration.

How did George Martin respond to the mandola? (Martin produced the second and third Seatrain Albums for Capitol Records after working with The Beatles).

Well, George had an aversion to the instrument. He said every time he heard the mandolin [affecting a British accent] “It sounded awfully much like an Italian wedding or funeral.” He didn’t like what he called a “plectrum” instrument. He didn’t like the “diddle diddle” sound.

Yet he played all that Baroque style harpsichord and piano on The Beatles’ albums.

Perhaps that stuff is better interpreted on the piano which has a more universal sound. The mandolin has those connotations. Every time I’d pick it up, George would say [in a British accent] “Gondolas!” [laughs]. “Peter, we are not in Venice!” But I wrote a lot on the mandola during that period. Songs like “Awake My Love,” and stuff I later recorded with Grisman and [Jerry] Garcia on an album that came out in Italy called Texican Bad Man.

After Seatrain you were in Muleskinner [with Clarence White] and Old and In the Way. Both bands featured Grisman on mandolin, so when did you finally get to play and record with your mandola?

With the Rowan Brothers I played mandola on a song called “All the King’s Men/Mongolian Swamp.” We did three albums for Asyulm Records and by the last one everyone was saying, “Put that mandola away!” It wasn’t the Brothers, it was the producer saying “This isn’t commercial!” [Laughs]

What kind of mandola is it?

A 1924 Gibson H-5. I haven’t had it worked on for about five years and the frets are a bit out of whack. They need to be dressed. I keep it tuned in octaves. I had a band with Tex Logan and the whole time I was carrying my mandola and hardly ever playing it until I went to the British Isles with Keith and Rooney as their mandolin player. Actually in my case, it was a mandola. It was great, my chops started coming back. We went to the Avery stone circle in Wales where I felt some strange mystical thing happening while Bill Keith explained the circle of fifths as we walked around this great stone circle. On that trip I broke a string and couldn’t find a replacement. I used a banjo and high E guitar string together, but try as I might I couldn’t tune them up to A. This changed everything. I began tuning the mandola with three pairs of octave strings and on the top, the A was tuned to a fifth! It was really great I could hardly play a bluegrass break ‘cause it sounded like steel drums! [Laughs] I started playing things that I heard in Greek music that Jody Stecher and Andy Statman turned me on to.

Can you talk a little about your playing style?

I mostly cross-pick. But I’d like to get an electric amplification set up on the mandola where I use and octave divider and a stereo chorus to flatten out the sound of the instrument and the scope of what you hear electronically. It would bring out the guitar-like qualities of the mandola and give it a broader sweep of sound.

Then why not just play guitar and, uh, “Put that mandola away!” What makes the instrument special for you?

It suggests a different mood. I relate to instruments and how they help you to write songs. individual instruments like the piano, guitar or mandola open-up different feelings for writing.

Have you been writing much on the mandola lately?

In Naples, I wrote “The Dance of Pulcinella” and a tango called “Antonella…” I also wrote one called “Primavera del Amore,” which Andy Statman played with me as a duet on an Italian release called Peter Rowan and the Wild Stallions.

Any other thoughts about the mandola come to mind?

For me, the mandola is a cipher of musical history. It has such a strong tone and color, and with octave strings, the way the chords fall on it, the depth and darkness of its tone… well, it’s a door opener. It’s a dolphin, or a stallion. It’s a rocket ship!

This interview took place in Marblehead, Massachusetts on September 16, 1984 (the night author Richard Brautigan died). A few years later, Peter’s beloved Gibson Mandola was stolen.

John Kruth

Latest posts by John Kruth (see all)

- Aboard the Mandola Rocket Ship - June 18, 2020

- Busted Strings & Crazy Gods: A Lost Interview with John Prine - May 20, 2020