“Country Blues” by Doc Watson

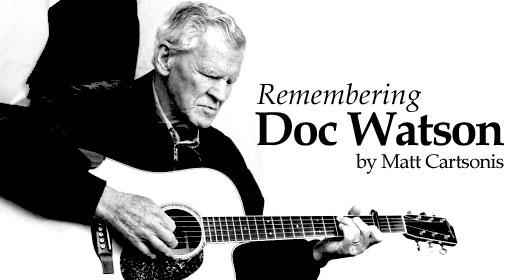

Remembering Doc Watson

By Matt Cartsonis

Doc Watson left us a week ago. By now everybody remotely into NPR or acoustic music has heard of how his first banjo was made from the esteemed skin of a favorite family cat, and that (and in his case one hesitates to say despite his blindness) Doc brought the same craftsmanship to building, wiring and repairing houses and furniture, as he did to the guitar playing that so fundamentally altered the course of American roots music. They know he was a genuine, down-home, nice fellow who had no real desire for mainstream stardom and wanted little more than to provide a decent living for his family. And they know he was pretty damn good at pretty much anything he tried.

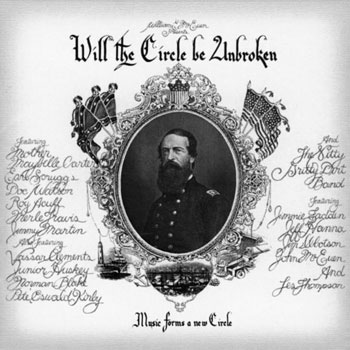

I first heard Doc Watson in 1973, as a young teenager in  semi-rural Arizona, when my best pal, Tom, came home with a copy of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s Will the Circle Be Unbroken (the first one—the best one). The album that had almost all of country music’s then-living originals on it: Roy Acuff, Mother Maybelle Carter, Jimmy Martin, Earl Scruggs, Merle Travis and Doc Watson. It was nothing less than a revelation to us—a chance to hear the kind of music we got from “Hee Haw” and the “Buck Owens Ranch Show” up close and conversationally. These guys were never, not in a million years, ever going to come to our town—the freeway hadn’t come to us yet, and we still had to go through the operator to call Phoenix. What we knew of the outside world came either over the broadcast waves or pressed into the grooves of shrink-wrapped vinyl. And a lot of the stuff that drew us in was rarely, if ever going to get on TV. It was a good year or so before I, at least, figured out that you could hitchhike into town if your folks didn’t find out, because music did come to Phoenix. But, that’s another story.

semi-rural Arizona, when my best pal, Tom, came home with a copy of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s Will the Circle Be Unbroken (the first one—the best one). The album that had almost all of country music’s then-living originals on it: Roy Acuff, Mother Maybelle Carter, Jimmy Martin, Earl Scruggs, Merle Travis and Doc Watson. It was nothing less than a revelation to us—a chance to hear the kind of music we got from “Hee Haw” and the “Buck Owens Ranch Show” up close and conversationally. These guys were never, not in a million years, ever going to come to our town—the freeway hadn’t come to us yet, and we still had to go through the operator to call Phoenix. What we knew of the outside world came either over the broadcast waves or pressed into the grooves of shrink-wrapped vinyl. And a lot of the stuff that drew us in was rarely, if ever going to get on TV. It was a good year or so before I, at least, figured out that you could hitchhike into town if your folks didn’t find out, because music did come to Phoenix. But, that’s another story.

There was just something about Doc Watson on that recording. When he meets the fabulously influential Merle Travis for the first time and tells him he named his own son after Travis and Eddie Arnold. I hardly knew anything about Country Music back then (didn’t even know that was what it was I was learning to play—it didn’t matter; it was all just part of the landscape), but could tell that this ad-lib conversation, thankfully caught with tape rolling, meant something, somehow.

And then there was the music. It was just so… good. Impossibly technically amazing little portholes into the Scotch-Irish roots of southern Appalachia. The music’s imagery on the surface, having so little to do with central Arizona, but picking amazing enough to keep me nailed to my seat long enough for it to actually sink in. There was something about the words and tone and delivery that transcended the medium. You couldn’t see what was going on, or what mattered about what was happening there, but you could hear it. And it all made sense. The history of lives and music intertwined and connected over time and space, in a moment in our history when that sort of thing was finally possible; where physical proximity was no longer an absolute prerequisite to mentorship and the handing down of tradition.

And then there was the music. It was just so… good. Impossibly technically amazing little portholes into the Scotch-Irish roots of southern Appalachia. The music’s imagery on the surface, having so little to do with central Arizona, but picking amazing enough to keep me nailed to my seat long enough for it to actually sink in. There was something about the words and tone and delivery that transcended the medium. You couldn’t see what was going on, or what mattered about what was happening there, but you could hear it. And it all made sense. The history of lives and music intertwined and connected over time and space, in a moment in our history when that sort of thing was finally possible; where physical proximity was no longer an absolute prerequisite to mentorship and the handing down of tradition.

That was a big deal to a kid like me, to suddenly realize you didn’t have to be from somewhere to be part of something. For me, Doc, along with Pete and Mike Seeger, was a direct line to the South East. He made me want to know more. His playing, speaking, kindness and geniality made this place where high lonesome music came from warm, friendly and interesting. He delivered me from Deliverance.

Do c Watson was everywhere. I started to teach myself guitar, with the help of Jerry Silverman’s “The Flatpicker’s Guitar Guide.” Doc was on the accompanying LP, singing and playing “Everyday Dirt.” Then, my cousin from California left a copy of Oak Publications’ “The Songs of Doc Watson” at our place. That thing was gold. It had transcriptions for “Black Mountain Rag,” “Doc’s Guitar,” “Blackberry Rag,” stuff that at 14, I was never going to figure out for myself.

c Watson was everywhere. I started to teach myself guitar, with the help of Jerry Silverman’s “The Flatpicker’s Guitar Guide.” Doc was on the accompanying LP, singing and playing “Everyday Dirt.” Then, my cousin from California left a copy of Oak Publications’ “The Songs of Doc Watson” at our place. That thing was gold. It had transcriptions for “Black Mountain Rag,” “Doc’s Guitar,” “Blackberry Rag,” stuff that at 14, I was never going to figure out for myself.

As I grew and developed as a picker, (and started sneaking out of the house and out of the neighborhood more regularly) I started to get to know the music community around the state. Doc, and what he had shared, was a big part of our common language. A vernacular I knew I’d never outgrow. There was no way.

Through his years, Watson never himself stopped growing. To this day, one of my favorite recordings is of Doc and Clarence White (who started where Doc left off, mixed in a little Joe Maphis and a lot of magic and completely revolutionized bluegrass guitar), jamming at a festival. Doc’s influence on Clarence is well known, but you can actually hear Doc bringing aspects of White’s technique into his own playing, years later.

That ego-less back-and-forth is something we can all learn from, inside or outside of music. That is what it’s all about.

I only met Doc Watson once, briefly, on my 28th birthday, when he came to Scottsdale for a club gig. We shook hands. I was basically speechless. Maybe said, “Thanks.” And I remember his grip, and his voice, and I have no recollection what he might have said to me. And it doesn’t matter. I already knew who he was—he was one of those exceedingly rare people who are face to face the same person they are in print and on stage. A natural, nice, dedicated, hard-working guy who really cared about what he was doing, and shared those values with anybody ready to receive them.

89 is a ripe old age. But it was too soon for Doc Watson to be taken from us, because we will always need him here. Lucky for us, his legacy and lessons remain.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

About the Author: Composer and multi-instrumentalist, Matt Cartsonis, has spent his life dedicated to his craft. A highly regarded, versatile songwriter and producer, Cartsonis’ work can be heard in countless features, documentaries, TV shows and commercials. Mentored by Pete Seeger, Cartsonis is one of LA’s most respected “sidemen” and has played with legends such as Warren Zevon, Steve Martin, Glen Campbell, The Kingston Trio, John McEuen (Nitty Gritty Dirt Band) and Van Dyke Parks, to name only a few. For more information on Matt, read our Sin City Spolight or visit: http://www.mattcartsonis.com

Latest posts by TJ Staff (see all)

- Song premier: Brooke Graham – “Merryachi Christmas” - October 31, 2022

- Sean Devine’s Here For It All - September 7, 2021

- Video Premier: “No One Gets Pulled Over on Christmas Eve” (The Smoking Flowers) and “Santa Claus is Dead” (Dee Oh Gee) - December 22, 2020