“If you ever get really depressed, put on a Terry Allen album. It will just make you smile. His sense of humor, way with words, and the situations he writes about, it’s priceless.” – Guy Clark

Terry Allen speaks with the same Texas drawl he sings with. His voice is rooted in where he came from. But it’s what he says in that voice that goes into its own unique direction. His descriptions of his life, told with sharpness, reflection and a keen sense of humor. His unparalleled storytelling, cleverness, piano playing and the many different mediums he uses to express himself, make him Lone Star State’s most complete artist.

But there is no one better suited to describe Allen than his friend, Guy Clark, who had a conversation with us, before his passing in 2016. Clark recalled the first time they met.

“It was at the Kerrville Folk Festival. We were sitting in the lobby of the Hilton in Kerrville. We were waiting on the ride out to the festival. We started wandering around the couch in the center. I knew who he was. We finally introduced ourselves. We got to talking. We stayed up all night, playing songs and drinking whiskey. We just had a wonderful day.”

What is so special about Allen, Clark describes in a way that no one else could. With simplicity and authenticity.

“He’s one of the coolest guys in the world.”

“He’s an artist. He truly is. The way he is, everything is art. It’s wonderful to be around. Terry’s personality is the same as it is in his artwork. He’s really funny. He’s just one of those guys from Lubbock. He’s everybody’s hero.”

Clark was referring to the fact that Allen attended Monterey high school ahead of Texas musicians Joe Ely, Jimmie Dale Gilmore and Butch Hancock, who would carve their own path in music as the Flatlanders. A name appropriate to the environment Allen describes growing up in.

“Lubbock is so flat, that on a really clear day, you look in any direction, and if you look hard enough, you can see the back of your own head. That kind of thing, filters through the world back into you. It makes you want to make something.”

Allen’s time in Lubbock forever shaped the way he approaches art. The juxtaposition of his worldliness and southern sensibility, give him a creativeness inequitable to anyone else.

“As an artist, visually,” Allen says, “since there is nothing in Lubbock except horizon, it’s that horizon that has a tremendous impact on you. It makes you want to see what’s on the other side of it. Any of the curiosity you have, you’re drawn elsewhere. When you’re raised without an obstruction between you and the horizon, you do actually see and perceive things differently. It’s more expansive.”

The way of life Allen was exposed to, contrasts where he ultimately wound up as an artist. Allen’s observations of the people, their views, and sometimes prejudice, driving many of the stories he has told throughout his career. His take on situations and conversations that may seem ordinary to some, are brought to life with unparalleled interpretation set to music.

Allen processes his surroundings in a way that allows him to create characters that are meaningful in spite of being otherwise viewed as commonplace. In some ways, it’s as if Cormac McCarthy wrote satire. With his use of characters, there is no distinction that a person’s life is either mundane or significant.

“Lubbock is like a world of paradoxes,” he explains.” You can sit down and hear the most remarkable stories. The sweetest stories. Then, the same person will say the most racist, Right Wing garbage. It’s always a balancing act when you’re in Texas. And I’m not sure America isn’t the same way. People.”

“The epic conservatism,” he continues “and boredom and religious fanaticism influenced me as an artist. Influenced me to get out of there as quick as I could,” he laughs.

Many of the songs Allen has written over the years, take a comical approach to the religious fanaticism he grew up around. The album Salivation features a smiling Jesus on the cover. The song, “Gimme a Ride To Heaven Boy,” about a hitchhiking Jesus, came from Allen’s peculiar imagination.

“I was driving one night between Fresno and Los Banos, some guy pulled up next to me, his light was on inside his car and he had a thousand little bandages on his face. He turned and looked at me like some Steven King deal. It was really very spooky. And then I just kind of floor boarded it and I started singing ‘gimme me a ride to heaven boy.’ That’s where it came from.”

The cognitive approach Allen takes, started at an early age and has continued throughout his life. Whether it is writing, drawing, playing music, or making a sculpture, it doesn’t matter to him, it all becomes one thing, all about the choices he makes selecting a medium. But at the forefront of his creativity, is his ever present awareness.

“I don’t see how you could help that wherever you are what you’re around, whatever you hear, not having an impact on you. That’s where all your tools and senses are. I don’t think it’s necessarily immediate. You can overhear a conversation and just follow it away somewhere or write it down. Someone behind you talking about something you don’t realize until four or five years later, that it is something that’s valuable to you or that you can use. That’s the nature of the mystery of it,” Allen says.

“Stories are so different. One story can be told with a sound and an image. Another story can be told with 1,000 words. I think what you try to do is find the truth of whatever it is you’re trying to say. Try to find it, part of it and then gear whatever thing you’re working with, toward that, and be as true to the heart of that as you can.”

DISEASE OF THE DREAMS

Well he took his first release on a highway in a 1953 green Chevrolet

An he was carryin and awful load for just a 15 year old

‘Til he laid his mind on the center line and turned up the radio

Goin’ a hundred miles an hour own the blue asphaltum line listenin’ to the Wolfman of Del Rio

And he didn’t give a damn about the trouble he was in

Yeah deep down in his soul he just wanted…to go

And you can tell by the look on his face he’s all caught up with the need

To trade in some emptied out spaces for some speeeeeeed

And that good ol’ American DreamTerry Allen, “Wolfman of Del Rio”

“Wolfman Jack was this voice that came from Mars,” Allen says. “You had no idea who this person was, where they were. You knew he was in Del Rio, and that there was a big transmitter across the border. But you didn’t know if it was a guy, girl. The nature of his voice was so strange when you first heard it.”

“In the middle of the night you’d be driving down the highway. Wolfman Jack would come on from 11 o’clock at night to one in the morning. Right in the middle of some song you’d never heard before, some deep Delta Rhythm and Blues or Lightnin’ Hopkins, he’d put a wolf howl. It was always at the right spot. It had a huge impact, most of my peers you talk to and talk about Wolfman Jack and those radio stations, brought that inspiration to you.”

The birth of rock ‘n’ roll changed Allen’s life. It opened the door to possibilities in the world that he had not been exposed to. For the first time, he was able to see a real gateway out of Lubbock, and connect with an art form on a personal level.

“It was the first time that the world had to do with you. Not all of this stuff that had been laid on you. It was the first time you ever heard music that was really about you. Your life, now. It wasn’t just ‘god, family, church and school.’ It was flat out, about you.”

“I remember hearing ‘Blue Suede Shoes’ the first time. I remember hearing Bo Diddley, ‘Hear What I Say,'” Allen recalls.

“Those songs went through you like an electric current. It was like a bomb dropping inside of you.”

“When Elvis first came about, he unlocked so many doors in the south, rural areas, where people were pretty much isolated, physically as well as mentally. Those songs, just burned down those little towns. People started wanting to play guitars, wanted to play something, be a part of that world. It was a very unique time. Because of radio, that was the first time you had a sprawl of radio across the country with the outlaw stations across the border. So people were hearing things that they’d never heard before.”

Allen most connected with guitar players such as Chuck Berry and Bo Diddly. The visual impact of watching them play, would shape him as a musician. His piano playing, coming from the influence of guitar. He viewed the instrument, as a performer. But Allen ultimately didn’t play guitar, due to the musical upbringing he came from.

“I only had a piano in my house, and I begged my mother to teach me to play it, because I felt like I had to play music,” he explains. “She taught me how to play the ‘St. Louis Blues’ and said ‘Now you’re on your own,’ basically. To me, that was what all of rock and roll was in those days. You get some rudiments of how to do something and then you’re on your own, to make it do what you want it to do and make you take it wherever you wanted to take it. It gave you freedom. It was a lifesaver in that sense.”

In high school, Allen started writing songs. The songs, coming from a place of rebellion.

“All the songs I wrote in high school, were basically written to cause trouble,” he laughs. “To irritate the powers that be. And make my peers laugh.”

The first song Allen wrote that he considered an actual song, was “Red Bird,” which he wrote in 1962. From there, he stared working on writing songs. When he left Lubbock for California, he played in a band. It was at that point, he decided how he wanted to live his life.

“Whatever happens, I want to be an artist, I want to be a musician, I want write,” Allen says. “Because I can’t do another fucking thing. This is what I do, because I can’t do a fucking other thing, I don’t know how.”

Allen Playing “Red Bird”

“I just wasn’t doing well in Lubbock. And I needed to get out.”

The way in which Allen would get out of Lubbock, came from a drawing class he took. This was the catalyst for his departure to California.

“I did terrible in high school. I did terrible except for an English class and a drawing class. I asked my drawing teacher, if there was a school like that class.”

“He had recently gotten out of Chouinard Art Institute (now, Cal Arts). He told me about that school. I applied immediately. I left before I heard if I was accepted or not.”

Allen points out, that growing up, he was never around visual art. This was apparent when he applied to art school.

“I’d never heard of any artists on the planet, other than Norman Rockwell,” he explains. “So, when asked who my favorite artist was that was the only name I could think of. My family got the Saturday Evening Post.”

Being in Los Angles during the 1960’s, had a tremendous impact on Allen. Coming from a small town and living in a big city, made him feel that he was in the middle of something he hadn’t before experienced.

“The world was erupting. Between music and the Vietnam War, everything was so volatile and exciting. It was incredible, the music, everything that was going on there.”

LUBBOCK WITH A VENGEANCE

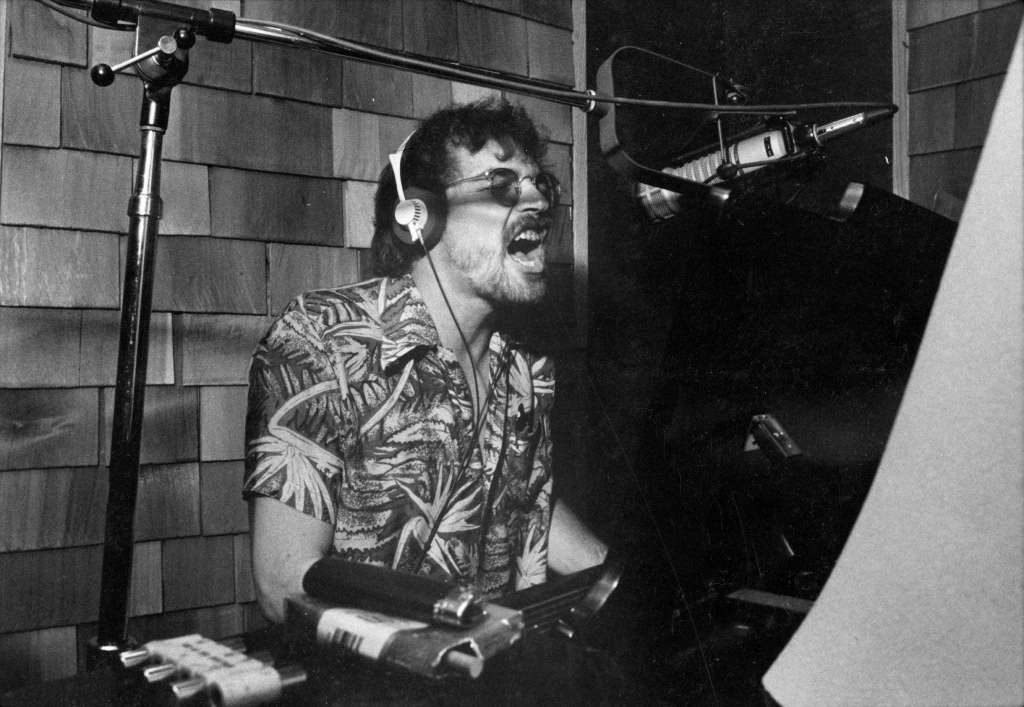

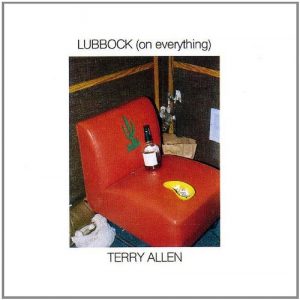

In 1977 Allen would return to Lubbock, to record his second album Lubbock (on everything). What he learned when he returned there, was unexpected.

“My view of Lubbock was ignorant in a sense,” Allen explains. “But I think every young person kind of uses wanting to get away from a circumstance, they inflate the negatives to force them to leave. That’s part of the deal. When I left Lubbock, I left with a vengeance. When I went back in 1977, I realized that the album was really about loving Lubbock.”

“My view of Lubbock was ignorant in a sense,” Allen explains. “But I think every young person kind of uses wanting to get away from a circumstance, they inflate the negatives to force them to leave. That’s part of the deal. When I left Lubbock, I left with a vengeance. When I went back in 1977, I realized that the album was really about loving Lubbock.”

“All this time I carried with me, that I had all these things I didn’t love about it. We recorded the whole album and listened to it. I thought ‘God this is really about caring about this place. This isn’t about those these kind of negative feelings I’d been hauling around. “

“You surprise yourself. A lot of times you think you’re learning one thing. But you’re learning something, totally different. And you don’t find out about it until later.”

Lubbock (on everything) is like Southern Gothic Literature, set to music and infused with humor. It is an album so unique, filled with snapshots of people’s lives, Allen’s experiences growing up and his surroundings, make it visual.

Listening to “Amarillo Highway,” it’s easy to imagine Allen driving down the wide open highway, with Rock ‘n’ Roll on the radio.

“The Beautiful Waitress” a snapshot of a chance encounter at a diner. “New Delhi Freight Train,” an odd take on the outlaw way of life. A song that stood out to Guy Clark.

“’New Delhi Freight Train,’ it’s such an interesting piece of work,” said Clark. “It’s really fun to play. The music, it’s really nice. But it’s the juxtaposition of the song.”

What Allen learned between the time he wrote “Red Bird” in 1962, to recording Juarez in 1972 and Lubbock (on everything) (released in 1979), was the evolution of his voice.

“Your voice is different. In your 20’s, 30’s, it’s circumstance. When people ask, ‘Why don’t you do a record like the one you did 20 years ago?,’ well, you can’t. Because you’re not the same person. You don’t have the sense of history. So your voice changes as your life changes and your music changes.”

BEYOND THE HORIZON

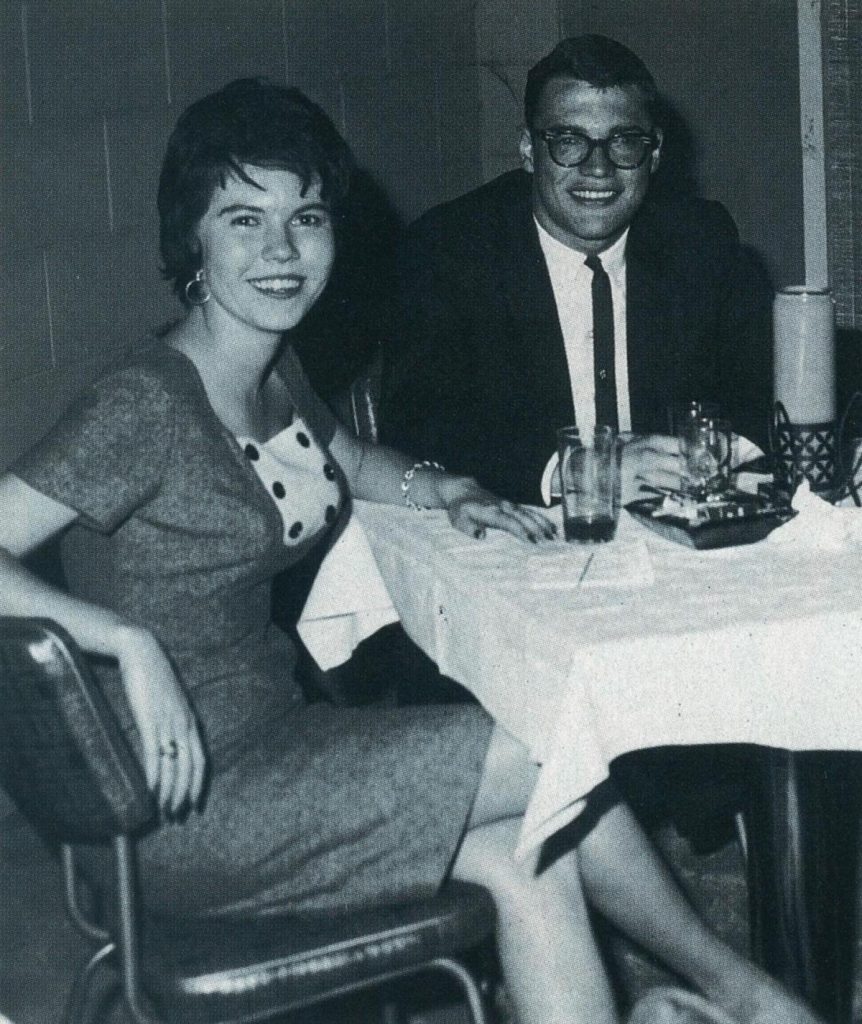

Today, Allen lives in Santa Fe, where he moved in 1987 with his wife, Jo Harvey Allen, who he met in high school. Their sons, Bukka and Bale Allen, are both songwriters and musicians who live Austin. But no matter where he lives, he feels most at home around his family and friends. If he’s around someone he cares about, he is at home.

One of the most special relationships Allen has had with another artist, was his friendship with Guy Clark. What Allen most appreciates in other artists, Clark had in spades.

“I think what always moves you about somebody else’s work, is the courage they brought to it,” Allen says. “The honesty they bring to it. The ability or skill they bring to it. Just the intelligence, doing something that you never thought of. When you look at something and say ‘Shit, I wish I’d done that or thought about that,” that motivates you to take those things into your own work. To give you courage with your own work, push your own ideas. That’s the nature of influence.”

A song that Allen collaborated with Clark on, came by way of tragedy. Clark was staying with Allen in Santa Fe at the time.

“He had his own studio. It was a Sunday morning, New Year’s day [1999]. Terry came out into the studio. I heard him say, “Some son’ a bitch shot my dog,’” Clark recalled.

“And I said ‘What? What?’ He said, ‘Yeah man somebody shot Queenie. She crawled up under that tree and died.’ I got up and we sat there,” he continued. “The only thing we could think to do was write a song. So we wrote ‘Queenie’s Song’ right there.”

“That’s the only thing we could think to make it right. We were retaliating with the lyrics,” Clark said.

“The whole song’s true. Everything about it. Except I never found the guy that shot the dog,” Allen laughs.

“Queenie’s Song” was recorded by Clark on his album The Dark and by Allen on Bottom of The World.

Allen plays “Queenie’s Song”

For Clark, the craziest memory of Allen he could recall from their friendship, happened on a trip they took to Italy with Susanna and Jo Harvey. They were traveling along playing songwriter shows. The last night of the tour, they played a fairly big concert.

“Terry got so mad at the people, because in his contract he had a certain keyboard that they didn’t supply him with,” Clark explained.

“At the end of the night he was so mad, he picked his keyboard off the stand, threw it on the stage and started dancing on it. He was so pissed by the way he’d been treated.”

When Allen isn’t destroying keyboards, he continues to create art. Be it visual, musical or written, it’s how he lives his life.

“It’s what I do. It’s there. I’ve done it for so long, it’s just part of the air. There’s no difference between painting, writing. It depends on the idea of what the story is or what you are trying to do. They inform each other so much. It’s always open for one informing the other. They come out of one another. It’s hard to say one is better or more or that they feel different. Sometimes I do one, sometimes I do the other,” Allen explains.

“There’s one thing about making art. It has provided me with an opening to a lot of different worlds. I did a whole piece on wrestling [Ring]. I did a whole piece [Amerasia] on the Vietnam War about American veterans who were expatriates in Thailand. You find yourself, two years down the line doing or being involved in something that two years before, you never had an inkling that might happen. I think that’s a great way to be alive.”

Despite how much his life has evolved from his early days in Lubbock, Allen finds himself turning to the open highway, as a sense of comfort as he always has.

“When I feel myself getting jammed up and balled up and anxious and bummed out, I get in the car and move and drive it and get away from the physical place I’m in to another physical place.”

“By looking out the windshield, and seeing something different, seeing other peoples’ lives taking place, it puts you in a perspective that you’re not so important and that your problems aren’t so important and different from anyone else’s on the planet. So, you go back and deal with whatever it is you’re dealing with. That’s always been a good escape hatch for me. To calm myself down.”

When asked what the one thing people should know about Allen,

Guy Clark responded, “He really can draw.”

Terry Allen Website | Juarez and Lubbock (on everything) were re-released in 2016.

They can be purchased, here.

Courtney S. Lennon

Latest posts by Courtney S. Lennon (see all)

- Billy Joe Shaver: August 16,1939 – October 28, 2020 - November 2, 2020

- You Are About To Become Involved With Van Dyke Parks! - July 13, 2020

- The Hero of Texas Music History - July 23, 2019