By Courtney S. Lennon, Editor

Dale Watson is about 75 miles from Memphis, headed toward his new home, located less than a mile away from Graceland. Dalevis, as he’s known as in the Bluff City, is out on the highway, talking on speaker phone. The call drops after a few minutes.

“Sorry about that,” he says. “I thought I was going to be in Memphis already. I’m driving the bus. I’m always going in and out of cell reception on the road.”

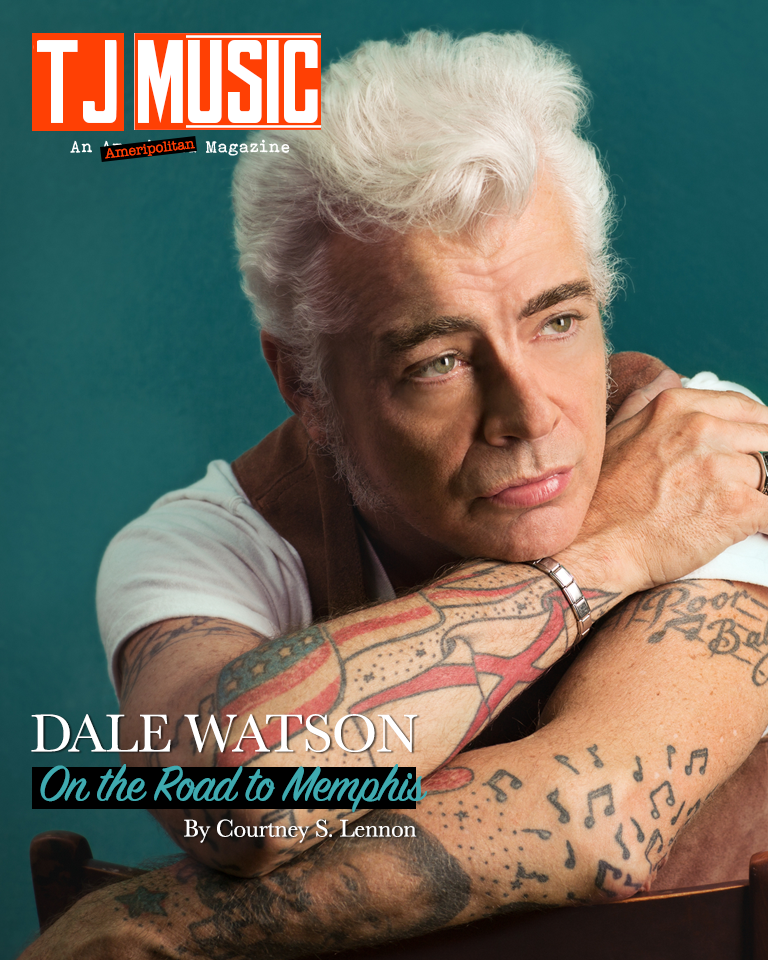

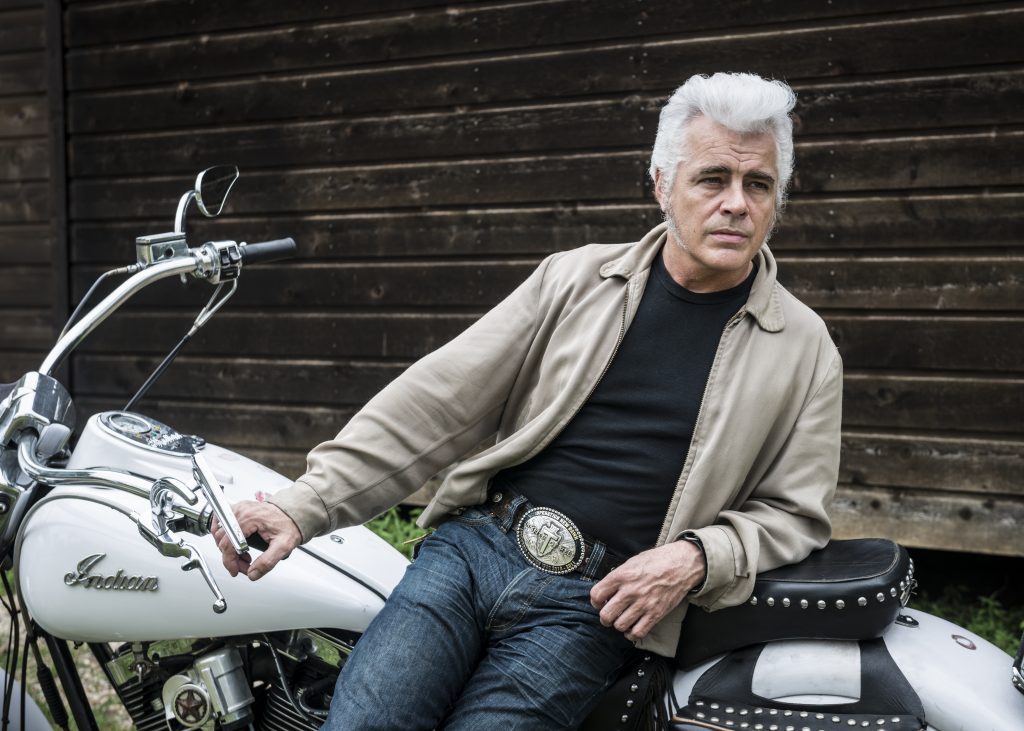

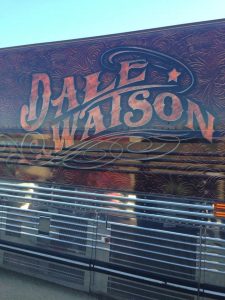

Watson speaks with the same deep twang he sings with. He has an easygoing vibe and a charming, dry, sometimes dark sense of humor. Conversation with him is relaxed. The stories he tells, free flowing. The southerner with a perfectly fixed white pompadour, is most comfortable in a t-shirt and jeans, sitting behind the wheel of his bus. Watson’s bus, with its elaborate paint job, is easy to spot from any angle. It says ‘Dale Watson’ all over it. The bus is probably the flashiest thing about him. It is also his home, for the 300 days out of the year that he tours with his Lone Stars. Driving it is like mediation for him.

Watson speaks with the same deep twang he sings with. He has an easygoing vibe and a charming, dry, sometimes dark sense of humor. Conversation with him is relaxed. The stories he tells, free flowing. The southerner with a perfectly fixed white pompadour, is most comfortable in a t-shirt and jeans, sitting behind the wheel of his bus. Watson’s bus, with its elaborate paint job, is easy to spot from any angle. It says ‘Dale Watson’ all over it. The bus is probably the flashiest thing about him. It is also his home, for the 300 days out of the year that he tours with his Lone Stars. Driving it is like mediation for him.

“It’s where I get the most ideas, for whatever I’m going to do. It gives me time to think. I’ve got a relief driver, who says ‘You want me to take over?’ and I say ‘No.’ He’s probably the most bored relief driver in the world.”

A longtime staple on the Austin, Texas music scene, Watson had an incident with his bus recently that gave him perspective. The city is changing. Fast. For years, he parked his bus in front of his house. But, as new people started to come into his neighborhood, they complained about the bus, which had been there long before they were. His old neighbors, never said anything, they understood it.

“I don’t like government in your business. That’s just happening more and more as the city grows. It is what it is. I found another property, where it’s parked and hidden. They can’t say anything about it. Well, not for right now anyway,” he laughs.

Watson has about an hour more of driving before he gets to Memphis. The next day, he will start to record his new album at Sam Phillips’ Recording, which Phillips purchased in 1960 after out growing his original Memphis Recording Service. The studio is only a five-minute walk from Sun Records. Watson, who has produced four albums at Sun, including Dalevis and The Sun Sessions, wrote 80 percent of the songs that will be on his upcoming release, while driving the bus, as he has done throughout his career. The album, he says, will be recorded in three days. It will include upright bass, acoustic and electric guitar, table steel and a guest spot from Johnny Cash’s only drummer, W.C. Holland (who also played with Carl Perkins).

“It’ll sound like Lefty Frizzell made a record at Sun. Because, you can’t shake the honky-tonk out of me.”

The day after recording, Watson will begin another long stretch of touring, heading first to Texas. Though he spent his childhood living in a trailer on a dirt road in North Carolina, at 13, he moved to Texas and has always considered himself a native of the state. Early on, he played music in beer joints, because his brothers and his father were honky-tonkers. He visited his father every summer, who lived in Jackson TN, which is about 80 miles outside of Memphis, not far from where Watson is driving. Another 130 miles east of Jackson, is Nashville. A city he could only tolerate for 10 months.

NASHVILLE RASH

Before Watson moved to Nashville, he went to Los Angeles in 1988, under the advice of Rosie Flores. It was there that he played as part of the house band at the Palomino Club in North Hollywood, a legendary venue that was known for alt-country music.

Before Watson moved to Nashville, he went to Los Angeles in 1988, under the advice of Rosie Flores. It was there that he played as part of the house band at the Palomino Club in North Hollywood, a legendary venue that was known for alt-country music.

“The LA scene had the same vibe Memphis has got right now,” Watson says. “In the 80s, Dwight Yoakam popped up on the L.A. scene and there was a real Bakersfield thing happening. And that’s what drew me out there. But it quickly got stomped out by line dances. So I went back to Austin, then went to Nashville.”

After having his first child, he thought he should be home more. So, he took a job with a publishing company in Nashville, where he’d write songs with strangers, for other people to cut.

“It was the most miserable time in my life. It seemed like a sweat house or a manufacturing house. No soul.”

In his song “Country My Ass,” Watson sings, “Now don’t get me wrong, to each his own I believe. But they’ve took the soul out of what means a whole lot to me. ‘Cause I can see Hank and Lefty, they’re spinning around in their graves. And if they were here, you know what they’d say? That’s country my ass.”

He was inspired to write “Country My Ass” after reading an issue of Enquirer Magazine in the waiting room of a dentist’s office in 1998. There was a page in the magazine titled “Things Overheard Backstage at the CMAs (Country Music Awards).”

“Merle was talking to Waylon. Merle said, ‘CMA should stand for Country My Ass.’ While I was in the dentist chair, I thought about the lyrics to the song,” he says.

Watson grew up on the music of Merle Haggard, Waylon Jennings, George Jones, Ray Price, Hank Williams and Johnny Cash. It was part of him. When he recorded his debut album, Cheatin’ Heart Attack in 1995, after escaping Nashville and returning to Austin, he was already taking on the mainstream country establishment. In the song, “Nashville Rash,” he sings “I’m too country now for country, just like Johnny Cash, help me Merle I’m breaking out in a Nashville Rash.”

As the years have gone on, country music has progressively gotten more atrocious. It is unrecognizable from what it once was. So, Watson created his own genre, Ameripolitan, which is original music with prominent roots influence. It encompasses classic country, outlaw country and rockabilly.

“The word ‘country,’ it’s just too late to take it back,” he says. “Country music today is mainstream and successful. To a point, the term is accurate now. It was called ‘country’ because people who lived out in the country were farmers who listened to Hank or Johnny. But nowadays, guys drive around in air conditioned tractors listening to Hick-Hop.”

Throughout his career, he has referenced the fact that legendary country artists are being left behind. On the song “Legends (What If..),” he mentions Willie Nelson, Charlie Pride, Loretta Lynn, Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, Buck Owens, Waylon and Conway Twitty. Back when he wrote the song, most of them were still alive. But aside from Lynn, Pride and Nelson, the other artists mentioned have since passed.

“Just because radio forgot them, it doesn’t mean we have to,” he says.

On his last album, which was a collaboration with Ray Benson (Asleep at the Wheel), Dale & Ray, they recorded a song called “Feelin’ Haggard” after the death of Merle Haggard. The song, not so much a tribute to Haggard, rather it is a song about losing someone important, who despite passing on will always be with you. When Haggard died, Watson and Benson were already in the process of making their album.

On his last album, which was a collaboration with Ray Benson (Asleep at the Wheel), Dale & Ray, they recorded a song called “Feelin’ Haggard” after the death of Merle Haggard. The song, not so much a tribute to Haggard, rather it is a song about losing someone important, who despite passing on will always be with you. When Haggard died, Watson and Benson were already in the process of making their album.

“Ray was very close with Haggard. I only met Merle a few times. So that day, Ray called me up and said ‘I just started a song, I want you to help me finish it.’ I’m glad because I attempted to write something because I felt like I needed to write something. But when he brought this to me, I said, ‘Man, I feel the same way.’ And so many people do.”

Always outspoken, he recently took on the Nashville machine when Blake Shelton called the people who listen to the type of music he has tried to preserve and carry on, “Old farts and jackasses.” At the time, Watson was on tour in Europe.

“I didn’t know who Blake Shelton was. I thought ‘Who is this guy? That he’d say something like that?’ They said ‘well he’s on a TV show. He’s one of the judges on that talent thing.’ I didn’t even know he was a country artist. I had no idea,” Watson says.

He read what Ray Price said of Shelton; “There’s not a hat big enough to fit his head.”

“Let’s see what Shelton’s music will sounds like in 65 years compared to Ray Price’s. No one is going to remember him in 65 years. No way. And that’s the way it should be.”

Price’s comment inspired Watson to write a song. A ‘knee jerk’ guy, he writes what he is passionate about. His retaliation, the song, “I’d Rather Be an Old Fart than a New Country Turd.”

FIXIN’ TO HAVE ME A BREAKDOWN

After his short, miserable stint in Nashville, Watson moved back to Austin, TX. He was drawn there because the city was progressive. Austin is known for good original music, where no matter the genre, there is an audience for. It was there where he got a record deal with High Tone Records in 1995. His first album was Cheatin’ Heart Attack.

The album, a pure honky-tonk release at a time when country music was rapidly on the decline. Music City was churning out pop music with steel guitars. Then there was Watson, the Nashville Rebel in the same vein as Waylon Jennings. Cheatin’ Heart Attack is raw outlaw country. It is the 90s equivalent to Honky Tonk Heroes, a record that defied everything modern, polished country music stood for. A self-proclaimed ‘control-freak’ when it comes to his sound, Watson produced the album, and the follow ups, Blessed or Damned (1996) and I Hate These Songs (1997). For the most part, he has produced all of his 30 some records over the span of his career as a recording artist with only a few exceptions.

Not long after he established himself as an Austin songwriter, while, going through a divorce with his wife of nine years, he met Terri Herbert. They immediately got along and fell in love. She accepted him, both the good and the bad. It made him feel special, having someone look past all of his faults and scars, and still loving him. Four months later, in September, 2000, she died in a tragic car accident driving to Houston. Watson was supposed to be with her, but was too tired. She wasn’t wearing a seat-belt, because her cellphone dropped and she tried to pick it up. At least that is the theory.

“It was quick. The thing about that relationship, looking back on it, you don’t have the scope when you’re in it. It was only the honeymoon phase of the relationship. We had four months together. So there was really no time for anything to go bad.”

During their relationship, Terri asked him to write a song about her. He told her, “You can’t just order up a song, that’s not the way it works.” He wrote the song, “Blue Eyes” about her. An improvisational songwriter, Watson writes around 20 percent of his songs on stage. His biggest commercial hit, and what is now considered his anthem, “I Lie When I Drink” was written on stage at the Continental Club in Austin. He was talking about Lone Star beer and a guy in the audience said “yeah but you lie when you drink.” By the second time he sang the chorus, everyone was singing along.

When Watson came up with “Blue Eyes,” Herbert, was at the show. It was the only one she got to hear written about her. He did not record it until after she passed.

Her death, sent a shock-wave through him. At first, he purged his emotions out, by writing the album Every Song I Write is for You, as a tribute to her. But instead of the process healing him, it ultimately took him to a darker place. On New Year’s Eve 2000, he tried to commit suicide at a hotel in Austin after writing the album and coming back from a tour. Luckily, he was unsuccessful.

“It hurt too much. So I tried to [kill myself]. I’ve never been a drug guy in my life. I’m really not much of a drinker. But I took sleeping pills and drank. But luckily, where if I take a sleeping pill, it does the opposite to me. People take Nyquil to go to sleep. It just keeps me up and makes me jittery. I happen to be one of those guys, where, if I take a sleeping pill, it does the opposite to me.”

After the suicide attempt, Watson was in the hospital. He would end up there again in less than two years.

“I didn’t have any say in that one,” he laughs. “When they found me out of my head, they took me there and checked me in.”

As he continues to drive the bus towards Memphis, he reflects on the darkness he faced with the same wit he possesses no matter the subject at hand. Whether it is the bus or perspective, he is uninhibited, talking about his suffering. Two years after Herbert’s death, he was in the hospital again, this time, by choice. Going through the mourning process, it all started with a Ouija board that made him believe he could contact the dead. He tried to search for ways to help heal, but then he began going to psychics who said he was talking to the dead. He read self-help books, quit drinking and straightened up.

“The self-help books are part of the reason I went crazy. I went really crazy, off the deep end, from trying to self-help myself.”

I’D DEAL WITH THE DEVIL

A good friend of both Watson and Herbert’s mother, said, “It’s two years after Terri’s death. And you’re still not over that?” He was not.

“That’s just not the way it works,” he explains. “You don’t ever get over somebody that you love passing, you just learn to live with it. At the time, nobody thinks that. But, the only healer is time. Time does heal, it doesn’t fix it, it doesn’t take it away, but you learn to live with it.”

Though he tried to overdose on drugs two years before, he then “overdosed on religion.” He became overzealous about God, which led him into psychosis. He was hearing voices. From Herbert, to his dad, to God and Jesus. No one else could hear the voices, but to him, they were audible.

“I was in Spain. The voice said that he was the devil. And that he was pretending to be all these people all along. I went to the Vatican,” he continues. “I tried to take the New Testament to the Pope. Luckily, I didn’t get arrested. I was doubting myself the whole time.”

It was at that point, that he realized he had lost his sanity. He was talking to Jesus, God and the Devil. He was being thrown all over hotel rooms from the voices, wherever he was.

“I asked myself, ‘Does a sane person really doubt his sanity?’”

The answer was “no.” So, he desperately tried to seek help. He went to two priests in Austin, but they turned him away.

“I said, ‘Look you aren’t going to believe me but the Devil is in my head and I can’t get rid of him. Can you do anything? An exorcism or whatever?’ But, they looked at me like I was nuts. Which was funny because the voice in my head, the devil was, just laughing, saying, ‘They preach about me all day long and try to tell everybody about me but when you tell them about me they don’t believe you.’ I was flabbergasted. I just was listening to this voice.”

After being turned away by priests, he was turned away by the mental hospital in Austin. They wouldn’t admit him or help him. They told him, despite his pleading, that someone else had to have him committed.

“I said, ‘Please you got to help me because the Devil’s telling me to hurt my friends, hurt my kids. I need help.’ But, they wouldn’t do it. They said I had to have somebody else do it.”

He called his ex-wife and asked her to do him a favor: have him locked up. She agreed to do it. But in order for him to be committed, she had to make it clear that he was a danger to her and their children. The voice in his head, the Devil, was telling him to hurt them. So he insisted that she bring his friends, Red and Billy to protect her.

Finally, he was admitted to the mental hospital, where he spent nearly 30 days. Even after his release, he still faintly heard the voice in his head, until he no longer gave it any power.

“At the end of the day, I deal with the Devil. It wasn’t real. These days, I keep religion at bay. Life is how you live it every day. I don’t worry about a guy in the sky, what he’s gonna think when I die. I’m much happier just living, trying to be a good person every day and do the best I can.”

BLUFF CITY BOUND

Watson’s drive is almost nearing its end. He should arrive in Memphis in about 20 minutes. Though he lived in Austin for nearly 30 years, it got too big for him. Much of what he loved, has been knocked down. Though he owned two clubs in Texas, the one in Austin has been sold and his San Antonio club is up for sale. Watson is considering buying a venue in Memphis, a city that is in the process of revitalization.

“There’s just a vibe there, a feeling,” he says of Memphis. “It’s always been an attractive town for me. It’s just got the roots. It seems like for a while, its roots weren’t appreciated.”

On the muddy banks of the Mississippi River, Memphis is a city that has a rich music history. It is where much of the music Watson appreciates came from. The Delta Blues was born out of the city during prohibition. Rock ‘n’ Roll was born, at Sam Phillips’ Memphis Recording Service, when Ike Turner walked in with Jackie Brenston and the rest of their band in 1951. The song “Rocket 88,” was the first Rock ‘n’ Roll song. Three years later, Elvis Presley walked into the studio. Accompanied by Scotty Moore on guitar and Bill Black on bass, Phillips created a country, rhythm ‘n’ blues fusion, with Presley’s recording of “Blue Moon of Kentucky.” From there, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins and Jerry Lee Lewis would all walk into Phillips’ studio and leave as legends. Just over two miles away from Sun, is Stax Records. Founded in 1957 by country fiddle player, Jim Steward as Satellite Records, Stax’s early releases were country and rockabilly records. Stax would later be the place where Southern Soul was born out of, with artists like Otis Redding. Pianist Booker T. Jones and Bassist, Donald “Duck” Dunn were the house band and were instrumental in developing the style’s signature groove.

Today, there is a burgeoning scene in Memphis again. Over the years, Watson has seen the city change. He now gets the same vibe that he did in Austin in and Los Angeles in the 1980s. It is the place where he feels artistically rejuvenated.

Only in Memphis, will one be able to see Dalevis perform with his band the Memphis 2 (a nod to Johnny Cash’s band). He calls Murphy’s on Madison in Midtown, “Mi Casa Segundo.” When he is in the 901, he enthusiastically plays free shows there. With Dalevis in town, the music scene has an advocate that could be no more suited for it. A blue collar town, that has adopted the slogan, “Grit ‘n’ Grind,” from its basketball team, the Memphis Grizzlies, located right on Beale where you can drink a beer outside and walk over to see a game. Watson’s raw sound is at home in Memphis. And hopefully, no one minds where he parks his bus.

His new album will be out at the beginning of 2018. Until then, he will be on tour, writing new songs as he drives and plays shows. Memphis, will be as special as it once was, with Watson behind the wheel.

dalewatson.com | fb | tour | buy

Courtney S. Lennon

Latest posts by Courtney S. Lennon (see all)

- Billy Joe Shaver: August 16,1939 – October 28, 2020 - November 2, 2020

- You Are About To Become Involved With Van Dyke Parks! - July 13, 2020

- The Hero of Texas Music History - July 23, 2019