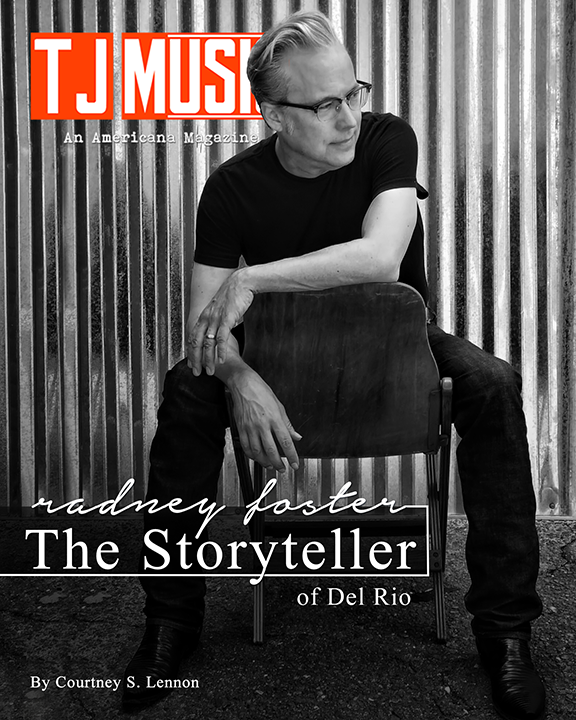

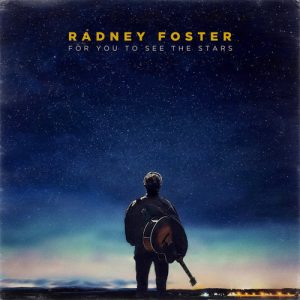

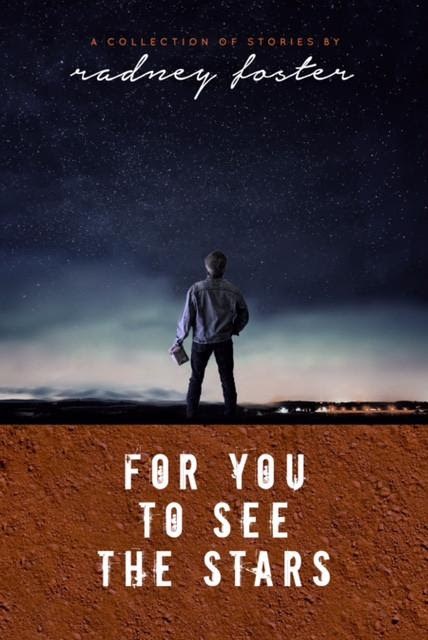

Radney Foster is at home in Nashville, Tenn., where he has lived for over 30 years. The Del Rio, Texas native, is in the middle of fixing supper, on a short break from touring. For the past few decades, he has often hit the road as a country singer-songwriter. He has penned top ten hits for himself and other artists throughout his career, but this time, he’s also on a book tour as a first-time author. His latest release, For You To See The Stars, is both an album and a book. The two versions work in concert, telling the same narrative in two different forms. The instructions are simple: read the short story, then, listen to the song that it is based on. Although both stand on their own, following the intended sequence reveals the uniqueness and inventiveness behind the project. As a listener, one is able to better understand the depth of each song by reading the correlating prose. For You To See The Stars lends insight into Foster’s process as a writer and who he truly is as an artist. But it wasn’t initially two pieces. Rather, it came about after he temporarily lost his voice.

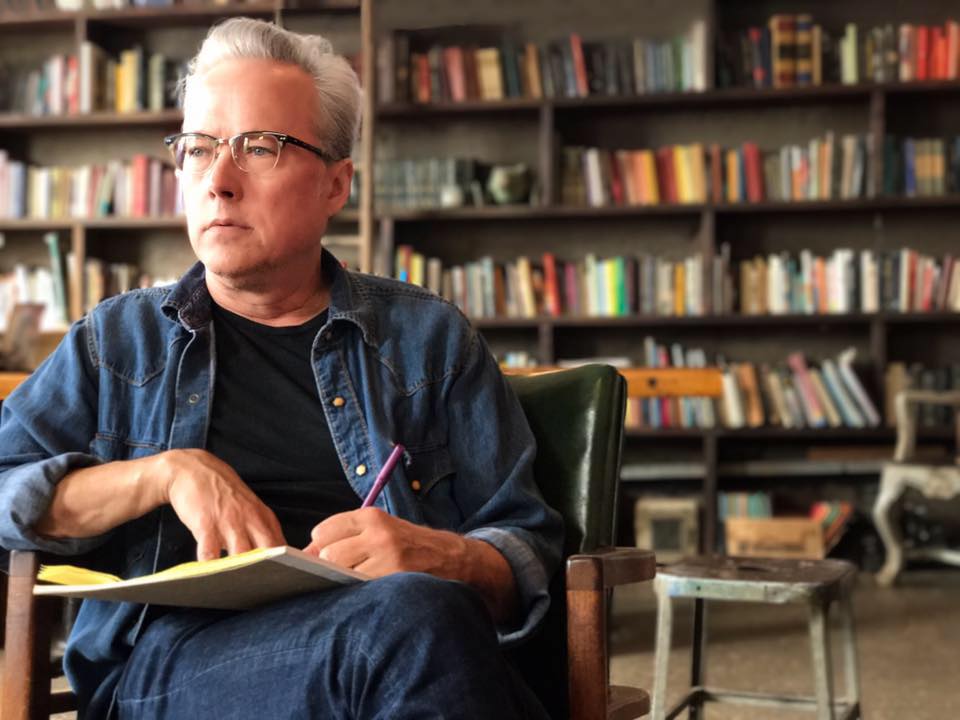

“It was an existential crisis,” he says. “I was about to record a new album that winter. I was touring to make some money to be able to pay for it. I had spent a few months before that, trying to really look at myself. Then, I get a case of laryngitis that was so bad, I couldn’t eat for six weeks and had to have physical therapy. It really messes with your mind, if singing is what you’ve been doing for most of your life. I couldn’t even hum to write a song. So I had to really start asking myself questions. I was trying desperately to figure out how to stay creative. ‘What if I never get my voice back? What if I can’t ever sing again?’ Then, I thought, ‘What do I really do? How do I continue to be creative?’ And I realized: I’m a storyteller. It really boiled down to that. That was when I made the decision to write a book.”

In much of Foster’s work, there is either a reference to Del Rio, Texas or it is the setting of a story. His first solo album, Del Rio, TX 1959, is a nod to both his birthplace and the year he was born. The album includes some of his most well known songs, “Just Call Me Lonesome,” “Don’t Say Goodbye,” and “Nobody Wins.” Del Rio, is a border town that lies on the northern most edge of the south Texas plains. It is composed of three very separate, but incredibly western landscapes. To the northwest, are the mountains of West Texas. To the northeast, Texas Hill country. Just south, is Ciudad Acuña, Mexico, a tourist destination where bands play traditional Mexican music. Though his father was a lawyer, Foster grew up around ranchers’ kids, riding horses, chasing livestock, attending youth group and playing music on the back porch. The cultural and musical influence of living in a Texas border town is evident throughout everything he writes. “It couldn’t help but affect me,” he says. “It’s seared into my heart”

On the album, For You To See The Stars, the song “The Greatest Show on Earth,” correlates with the short story, “Bridge Club.” They are about how he grew up in a musical family and reveal the power that music has in bringing people together, no matter what age they are or what background they come from. With guitar picking and mandolins, “The Greatest Show on Earth” captures the setting of Foster’s youth.

On the album, For You To See The Stars, the song “The Greatest Show on Earth,” correlates with the short story, “Bridge Club.” They are about how he grew up in a musical family and reveal the power that music has in bringing people together, no matter what age they are or what background they come from. With guitar picking and mandolins, “The Greatest Show on Earth” captures the setting of Foster’s youth.

“That song is as true as anything I’ve ever written. Only, I changed the name of my aunt, because I couldn’t make her name rhyme with anything,” he laughs. “Other than that, it’s pretty dang true. The fun part was, in looking for a piece of short fiction, I said, ‘Well, I’m going to write this as memoir, even though it’s fiction.’ What I wanted to accomplish was that, you’re sitting on the back porch with a bourbon late at night with someone who’s telling you stories about their dad playing guitar and is just spinnin’ yarns about his mama and daddy. That would be the voice; you’d hear it that way. My mom didn’t play anything, but she sang in church choir. My dad was not a great guitar player by any means, but he was a great singer. It didn’t matter if a song was country or Frank Sinatra. If it was easy to play and they liked it, my dad and his buddies would sing it. So that was my musical education, before I ever heard a record. Somebody brought the BBQ, somebody brought the potato salad, somebody brought the beer and everybody brought an instrument. That continued into my high school years. My parents were real involved with our church, so when we were all teenagers learning how to play songs, there’d be Wednesday night youth group at our house and we’d play. Then, on Saturdays, it would be multi-generational, just people sitting in a circle playing songs. That’s what you did for fun. From my older sister and her boyfriend, they were in their twenties; I was 14. Then there was my dad and his friends.”

“Bridge Club” shows Foster’s ability to weave comedy and tragedy together. It makes one laugh about a little boy peeing in the backyard. Then, it hits. Tragedy comes and at the end of it, the reader will be in tears. It is an example of how a story should be told. Whereas the child thinks he’s in trouble for peeing on his mother’s friends’ leg, fearing that his father has come home early to discipline him, that isn’t the case. Instead, everyone winds up in solace, because it is the day John F. Kennedy was shot.

“It is the tragedy that made me realize my own parents’ vulnerability. You write what you know. My earliest memory of my mom was when I was two-years-old. It was very sweet and hopeful. Then, the other was one was when I was four-years-old; my mother was crying violently. My father rushed home from work and my sisters came home early from school and people came to the house. It was my first brush with grief. I was terrified to see my mother cry so bitterly.”

If there is a common message in For You To See The Stars, it is that out of the ashes of tragedy, there’s still hope. In “Bridge Club,” by the end of it, everyone comes together playing songs, to heal or deal with reality. While Foster’s personality is upbeat and as infectious as many of the songs he’s written over his career, there is a dark undertone to the Southern Gothic stories he has written.

“Sorry, I read too much Flannery O’Connor as a child,” he laughs.

While “The Greatest Show On Earth” embraces the bond music has between people of all ages, the gritty rock and blues song, “Howlin,’” and the story, “The Night Demon,” explore the same theme in a different way. A child who has a small transistor radio, is told not to listen to rock ‘n’ roll. But at night, he lays in bed tuning into Wolfman Jack, the DJ that broadcast from Del Rio, playing what at the time was considered ‘the Devil’s music.’ As the child believes Satan is coming through the radio, he is conflicted whether or not he should listen to the music. When he finds out his mother is singing some of the songs he’s listened to, he thinks it’s his fault that the demons have invaded her. In reality, she has been listening to the same music.

One of the most poignant topics in For You To See The Stars, is addressed in the stories “Another Dragon To Slay” and “Sycamore Creek,” which come from Foster’s understanding of the tensions that derive out of the perception that Mexican immigrants are not Americans. The issue is timely in the current cultural and political climate, but it is something he has been cognitive of since growing up in Del Rio. “The racial component, families I discovered in later years, not until I was 40, that it turned out a friend of mine had been hiding the fact that he was part Hispanic, because his parents were terrified that it would mean a second class citizenship for him.”

One of the most poignant topics in For You To See The Stars, is addressed in the stories “Another Dragon To Slay” and “Sycamore Creek,” which come from Foster’s understanding of the tensions that derive out of the perception that Mexican immigrants are not Americans. The issue is timely in the current cultural and political climate, but it is something he has been cognitive of since growing up in Del Rio. “The racial component, families I discovered in later years, not until I was 40, that it turned out a friend of mine had been hiding the fact that he was part Hispanic, because his parents were terrified that it would mean a second class citizenship for him.”

In 1974, Foster began dating his first girlfriend, Déborah Hernández. “It was only a few years after the color line had dropped,” he explains. “It was a big deal for both her family and for my family. My family, even though we were Anglo, we’d been on the Mexican border for four generations. I was raised in a bilingual home. My father was adamant that you learned to speak Spanish because you couldn’t make a living in that town if you did not. 80 percent of the population, their first language was Spanish.”

In “Sycamore Creek,” he writes: “The hands mostly stayed to themselves and ate by a campfire in front of the bunkhouse, the barrier of language and legal status being a river too far to cross. The exception was our foreman Ruben and his family. Though the divide between Anglos and Latinos was wide, they gathered at the party tables like everyone else. Ruben’s daughter Déborah, who was two years behind us in school, interrogated Maggie and Miriam about San Antonio. A few other prominent Mexican American families who were business friends of my father’s were there. Ten years earlier they would never have been invited.”

Foster’s North Carolina editor, Shari Smith, called upon him to find a Spanish editor, because there was so much of it in the book. “She said, ‘I can’t even order off of a menu at a Mexican restaurant other than to point.’” That editor wound up being Hernández. In the acknowledgements he writes, “Thank you for editing my Spanish … and the great posole recipe.”

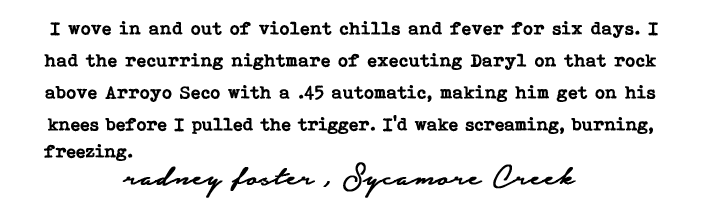

Redemption is a recurring theme throughout the book. “Sycamore Creek” addresses the inability of the character Daryl to achieve it, as he deals with homosexuality in small town, with a family that is too conservative to understand his struggles. Ultimately, his fate is determined by society. As he leaves his friends Maggie and Bobby Dean behind, they are left in to deal with trauma. Bobby Dean has vivid nightmares.

The subject carries on as a veteran suffers from PTSD in the story “Belmont and Sixth.” The pains of war, effected his life so deeply, that he wound up homeless, with a substance abuse problem. It comes up again, with a cop who buries the memory of arriving on the scene of a slain mother and her child, which led him to killing the father who murdered them, in a garage meth lab in “Requiem.” The cop appears immune to it, but his girlfriend thinks differently. She cannot understand why it doesn’t haunt him. The story, hearkens modern authors such as David Joy and Wiley Cash.

“It Ain’t Done With Me,” is set in New Orleans, a place Foster has visited many times. It places an ex-CIA agent, reconnecting with his daughter who he hadn’t been able to see since her birth due to his line of work. The story clearly stemming from his own experiences.

“I’ve always loved New Orleans and I’ve always gone there since I was a college kid, so it was pretty natural to write something set there. I had a child living in France for 13 years; I’ve been there a lot to visit him. I had joint custody, but he was taken at five years of age and lived with his mother in France until he graduated from high school. That was devastating and we tried to figure out how to be the best parents we could be from a continent away.”

“Slow Dance,” reflects the situation and emotion Foster went through as he cared for his ailing father who had long battled Parkinson’s. He passed away from cancer. Set in Del Rio, the main character, William H. Bell, also has Parkinson’s. Stricken with grief after his beloved wife passed, Bell has developed dementia and speaks for the first time in years, when he believes the nurse who is caring for him is his wife. The story, “For You To See The Stars,” finds a son trying to cope with the loss of his father, who, like Foster’s own father, was a lawyer. He writes, “The plane touched down and it jarred me from a deep, exhausted sleep. I felt those brief seconds of peaceful ignorance, those first waking moments of simply being before remembering that my father was dead. Daddy’s gone. I blew out a breath and the physical sorrow that follows death laid down next to my soul and began gnawing at me again.”

“We all suffer loss,” Foster says. “We all suffer trauma in some way. Our minds are such that there’s no telling whether that is going to trigger. Some people go through it and it never bothers them. Some people go through a car wreck and are terrified the rest of their lives. It doesn’t have to be the horrific things, but at the same time, it’s still trauma. I’m fascinated by that. I think, because I dealt with things that were hard in life. Some of them are normal. Losing my father was a terribly stressful thing for me. My dad was my best friend; I talked to him every day on the phone. I’m sure that I can’t help but inform those kinds of things from my own life, because you do.

For me, if you’re not digging around in your soul as a songwriter, you’re doing it wrong. When you’re writing prose and you’re making up these characters, you can’t help but find a piece of yourself in them.”

Ultimately for Foster, out of the crisis he faced losing his voice and the difficult experiences he has had throughout his life, he found the freedom of writing stories that exceeded the three minute format he had perfected throughout his career. His craftsmanship, apparent in his ability to write and revise, be it poetry or prose.

“I was always of the opinion that good songs are written and great songs are rewritten. The same holds true of fiction. As Hemingway said, ‘The first draft of anything is shit.’”

radneyfoster.com | fb | buy

Courtney S. Lennon

Latest posts by Courtney S. Lennon (see all)

- Billy Joe Shaver: August 16,1939 – October 28, 2020 - November 2, 2020

- You Are About To Become Involved With Van Dyke Parks! - July 13, 2020

- The Hero of Texas Music History - July 23, 2019